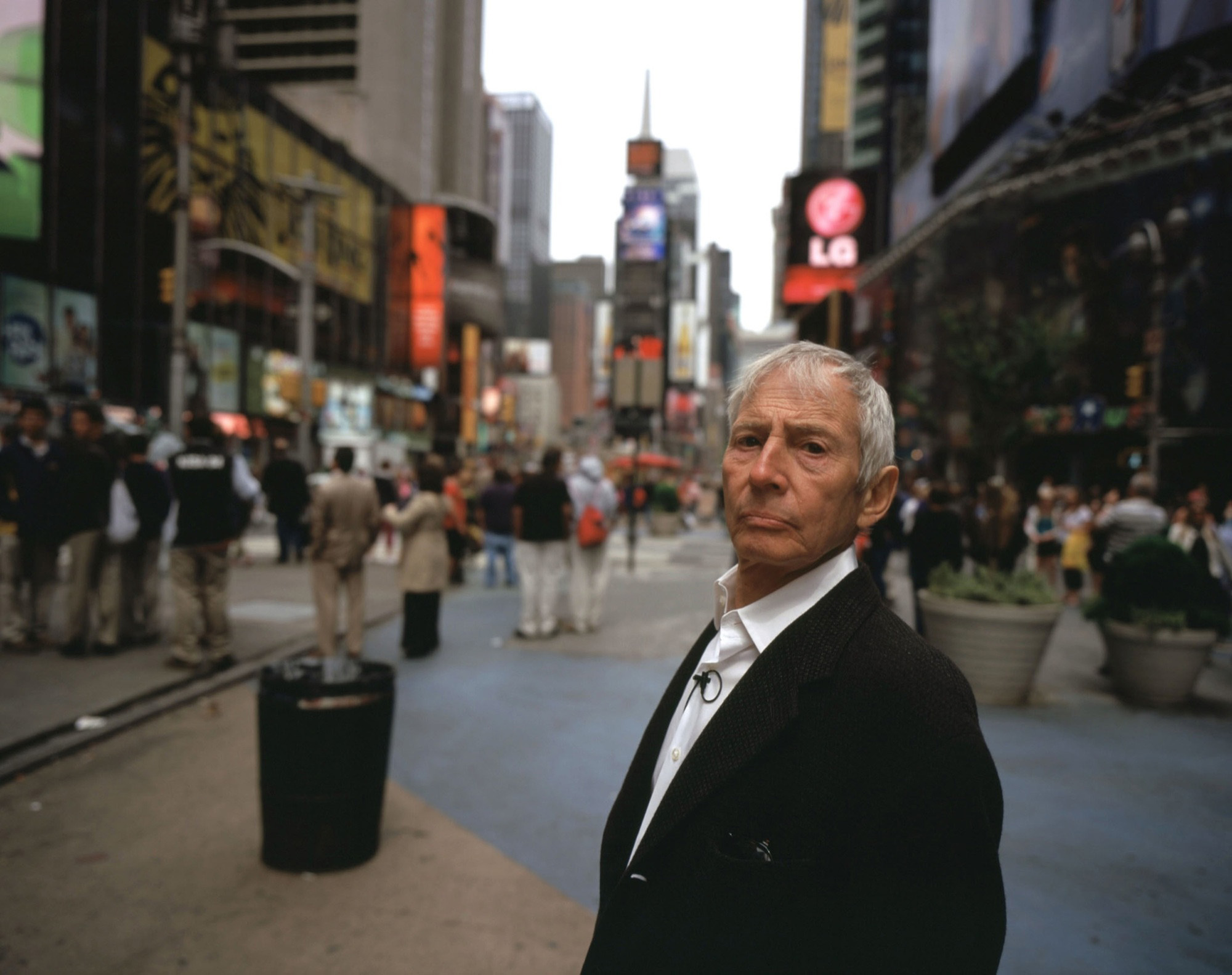

Will HBO’s “The Jinx” be the new “Serial,” the true crime

podcast that had everyone talking in 2014? The network sure hopes it will be. I’m

not sure. It’s not that the story of Robert Durst isn’t a fascinating one, with

bizarre twists and turns that fiction writers would discard from their outlines

due to lack of realism, but it’s almost too weird to catch on with a national

audience the way that “Serial” did. One of the genius moves of that podcast was

in how intrinsically it related to issues that felt universal, such as trying

to remember a specific day so many years ago. It focused on the

near-impossibility of putting pieces into a puzzle when those pieces have gone

fuzzy in the haze of memory. That was the hook of the first few episodes, which

then sucked us in with the specifics of the case. The hook of “The Jinx” is

more astonishment. It is body parts in bags, missing wives, and a figure at the

center of all of this who remains an enigma. Is Robert Durst crazy? Is he

brilliant? Is he both? Director Andrew Jarecki (“Capturing the Friedmans”) is a

talented enough documentarian that I know I’ll be there for all six episodes of

this documentary mini-series but I’m concerned after the first two that Durst

is a man for whom there are no real answers, and I worry that some of Jarecki’s

attempts to “pump up” this story with breathless anticipation of every twist

and turn and overcooked filmmaking effects (I hate the credits) are setting the audience up for disappointment.

In 2010, Andrew Jarecki made a film about Robert Durst

called “All Good Things,” starring Ryan Gosling and Kirsten Dunst. That film

focused on only one case that true crime aficionados know has been linked to

the enigmatic, bizarre Durst. “The Jinx” opens with another, the dismemberment

of Morris Black in Galveston, TX, a man who was living next to a quiet, older

woman who kept to herself, who also went missing at the time Black’s body parts

were found. It turned out that woman was Durst in drag, who maintains his innocence to

this day and remains free.

Durst also maintains his innocence in the first case in

which he was a suspect, the 1982 disappearance of his wife Kathie. The two

weren’t getting along—Durst even admits to physical violence on occasion—but he

maintains that she took off and not that he had anything to do with her likely

death given that she hasn’t been seen since in over 30 years. And that’s not even

it, believe it or not. Durst was also a suspect when his confidante Susan

Berman, a key witness in the first case, was murdered in 2000.

Perhaps the oddest element of “The Jinx” is how it came to

be. After seeing “All Good Things,” Durst contacted Jarecki and decided he

wanted to talk to him. And so this docu-series is not only made with his

cooperation but is built around an interview with him. He’s as fascinating an

interview subject as you’d expect—sometimes remarkably candid and forthcoming,

most of the time clearly withholding something and distant. And yet there’s

never any sense that he doesn’t want to be there. He wants to tell his story,

and yet it feels like he’s not quite telling all of it. Jarecki is an excellent

interviewer, making Durst comfortable enough and yet also asking the tough

questions.

I wish some of the flashier filmmaking aspects of “The Jinx”

weren’t quite so overcooked. The opening credits make this feel like an episode

of “Criminal Minds,” as do a few of the editing decisions and camera tricks. In

the end, this isn’t even really about these well-documented cases any more as

much as it is about two men—Andrew Jarecki & Robert Durst; the filmmaker

and the subject come together and are forced to dig deeper into their work and

background. On that level, “The Jinx” fascinates. Even though I know there’s

unlikely to be a real period at the end of this story, I’m curious to see where

Jarecki puts the ellipsis.