To donate to The Ebert Center, click here.

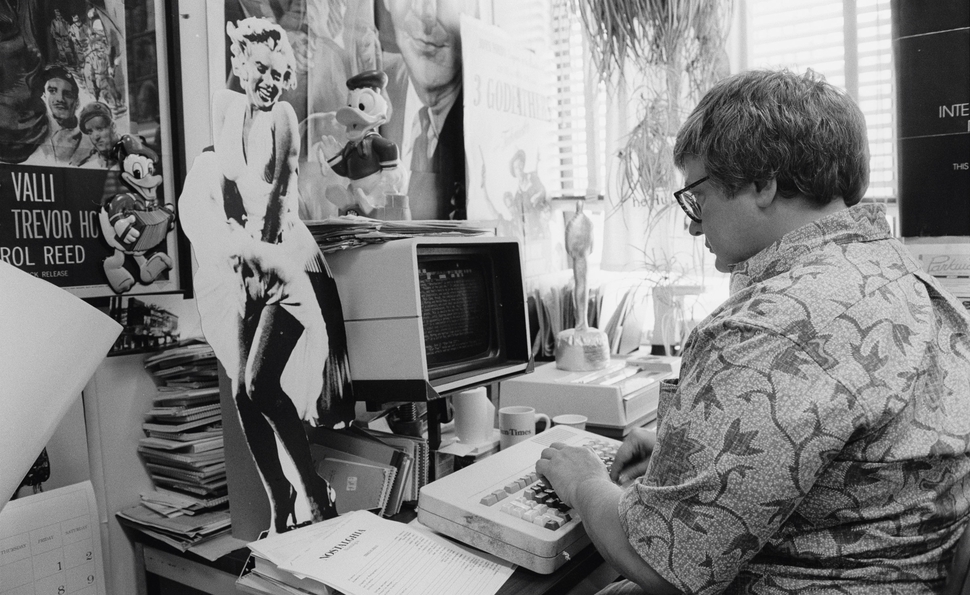

It felt right to commemorate the second

anniversary of Roger Ebert’s passing with a celebration of his work. The entire

front page of the site—which makes space for 13 reviews—is hereby given over to

Roger today and tomorrow. We’ve tried to select pieces that give a sense of the

length of his career and the breadth of his talent.

You’ll see a reviews here that you’ve encountered or heard quoted many

times, and some others that you’ve never seen before. Taken together, we hope they’ll give a sense of the totality of what he represented. While Roger’s work

was quotable, it was much more than that. His reviews say a lot in few

words. He had a knack for finding the essence of a film in a fairly tight

space, and for making singular observations that lodged in your mind long after

you’d read the piece, sometimes to the point where it became impossible to

watch or think about a particular movie without remembering what Roger said

about it.

“Galia” (April 7, 1967)

This is the first review Roger ever published

in a professional newspaper. He was 24. The opening

paragraph is vintage Roger, situating the film within the context of

then-current trends in filmmaking while also giving you a sense of how those

same trends were becoming tired through shallow misuse: “Georges Lautner’s Galia opens and closes

with arty shots of the ocean, mother of us all, but in between it’s pretty

clear that what is washing ashore is the French New Wave.“

“Bonnie and Clyde” (September 25,

1967)

One of Roger’s most famous early

reviews was of “Bonnie and Clyde,” a sardonic and tonally daring take

on a Depression-era crime spree that spoke directly to the spirit of the

late-’60s counterculture. Written by Robert Benton and directed by Arthur Penn,

the movie mixed jaunty populist anti-establishment comedy and shocking

brutality in a way that felt new. Although it was later treated as a milestone

and a masterpiece—a consensus classic—it was off-putting to many mainstream

critics at the time; few reviewers of any profile supported it with great enthusiasm.

The New Yorker‘s Pauline Kael was one. Roger was another. His review gives a

powerful sense of the movie’s unique energy—nobody who saw the film after

reading this could plausibly claim that he didn’t warn them what they were

getting into. But it also bridges the gap between straightforward,

consumer-oriented reviewing and the kind practiced in The New Yorker, The

Village Voice and Film Comment. In plain language, it explores

the film’s aesthetics, and connects them to what was going on at that moment

in the United States during an especially tumultuous decade, when violent

antiwar protests and bloody images from Vietnam were appearing in mainstream

newspapers and magazines and on TV screens.

“When

people are shot in ‘Bonnie and Clyde,’ they are literally blown to bits,”

Roger wrote. “Perhaps that seems

shocking. But perhaps at this time, it is useful to be reminded that bullets

really do tear skin and bone, and that they don’t make nice round little holes

like the Swiss cheese effect in Fearless Fosdick. We are living in a period

when newscasts refer casually to ‘waves’ of mass murders, Richard Speck’s

photograph is sold on posters in Old Town and snipers in Newark pose for Life magazine (perhaps they are

busy now getting their ballads to rhyme). Violence takes on an unreal quality.

The Barrow Gang reads its press clippings aloud for fun. When C.W. Moss takes

the wounded Bonnie and Clyde to his father’s home, the old man snorts: ‘What’d

they ever do for you boy? Didn’t even get your name in the paper.’ Is that a

funny line, or a tragic one?“

“Persona”

(November 6, 1967)

On the heels of his “Bonnie and Clyde” review, Roger published an

evaluation of Ingmar Bergman’s “Persona,” which might have been the Swedish

filmmaker’s most thematically and aesthetically daring work up to that point,

which is saying a lot. It was, by any measure, a difficult film for viewers

accustomed to conventional Hollywood stories and techniques; it’s still not an

easy sell, as any film professor today will tell you. But Roger eases the viewer

into Bergman’s mindset in a no-fuss way, explaining what the director is up to

in an accessible way that still preserves the mystery of the film’s effects.

“Most movies try to seduce us into

forgetting we’re ‘only’ watching a movie,” he writes, “But Bergman keeps reminding us his story

isn’t ‘real.’ At a crucial moment in his plot the film seemingly breaks, and

after it rips for a dozen frames it seems to catch fire within the projector.

We see it melting on the screen. Then blackness, then light and then the old

silent comedies again, as ‘Persona’ starts again at the beginning.“

“Who’s That Knocking at My Door?” (March 17, 1969)

This

is, to paraphrase “Casablanca,” the beginning of a beautiful

friendship. Roger was an early champion of Martin Scorsese—you can sense his

joy at publishing a regular review of a movie he first saw at the Chicago Film

Festival two years earlier—and when you read his review of “Who’s That Knocking

At My Door?” you can see why the director’s work spoke to him; why they

became close friends and stayed close even when Roger didn’t like his movies

(as was the case with “The Color of Money“); and why Roger would

eventually write an entire book about Scorsese and his films (2008’s “Scorsese by

Ebert“).

The

director and the critic shared certain life experiences, including a Catholic

upbringing and a youthful tendency to fear and/or idealize women, and perhaps

as a result, some passages here sound like bits and pieces of an

as-yet-unpublished memoir, or one of the tough-yet-lyrical, journalism-influenced

American writers that Roger loved so much: “[W]e enter a world of young Italian-Americans in New York City who sit

around and kill time and look at Playboy and

cruise around in a buddy’s car listening to the Top 40 and speculating

aimlessly about where the action is, or might be, or ever was. Occasionally on

Saturday night they get together at somebody’s apartment to drink beer,

watch Charlie Chan in a stupefied daze and listen to some guy who says he knows

two girls whom he might be able to call up. In this world, still strongly under

a repressive moral code, there are two kinds of girls: nice girls and broads.

You try to make the broads and you place the nice girls on an inaccessible,

idealized pedestal.” More intriguing still is an observation buried at

the end of the second paragraph, which may seem prescient to those who like

Scorsese’s early movies better than his later ones: “It is possible that with more experience and maturity Scorsese will

direct more polished, finished films–but this work, completed when he was 25,

contains a frankness he may have diluted by then.“

“3 Women” (March 15, 1977)

Coincidentally,

this review of one of Robert Altman’s masterpieces invokes Ingmar Bergman’s

“Persona” (see above), and showcases Roger, then ten years into his

career, easing into his role as American film criticism’s preeminent explainer,

masterfully giving viewers a sense of what kind of movie they’re about to see,

what they should notice about it, and why they should care about it. As in many reviews of Roger’s favorite films,

the filmmaking process and the director’s awareness of it are never far from

the writer’s mind, and yet these concerns never edge out Roger’s dogged

determination to tell us what the film is about, who the characters are, and what

it feels like to watch it. “The

movie’s story came to Altman during a dream, he’s said, and he provides it with

a dreamlike tone,” he writes. “The plot connections, which sometimes make little literal sense, do

seem to connect emotionally, viscerally, as all things do in dreams.”

“Blue Velvet” (September 19, 1986)

Roger’s

review of David Lynch’s “Blue Velvet” is often quoted by people who

never cared for Roger’s work, or who admired aspects of it but were frustrated

when he made what they considered bad calls on films that many considered great

or important. “Blue Velvet” was and remains a hugely influential

movie, a formative influence on more directors, films and television series

than can be listed here, but Roger just flat-out didn’t like it, because he

thought its scenes of “stark sexual

despair” were undercut by Lynch’s tendency to “[deny] the strength of his material or

trying to defuse it by pretending it’s all part of a campy in-joke.”

He was particularly incensed by the sexual abasement of the heroine, played by

Isabella Rossellini. “Rossellini

goes the whole distance, but Lynch distances himself from her ordeal with his

clever asides and witty little in-jokes. In a way, his behavior is more

sadistic than the Hopper character.” I don’t necessarily agree with

Roger myself, but every time I see “Blue Velvet”—indeed any film or

TV program in which women are sexually abused or humiliated—I think of this

review, which is not at all a bad thing.

“Do the Right Thing” (June 30, 1989)

Justly

regarded as one of Roger’s best and most significant reviews, this one spoke up

loudly and passionately on behalf of Spike Lee’s race-tinged urban drama,

praising it as a complex and worthy work of personal art at a time when many

mainstream media outlets seemed mainly worried about whether it was racist or

reverse-racist (it wasn’t) or might spark riots in theaters (it didn’t). What

registers most strongly today is Roger’s insistence that Lee be given the same

latitude afforded to any “serious” White director, to work through

his conflicted and contradictory feelings on a subject throughout the course of

a movie’s running time without being knee-jerk condemned for not being 100%

laser-focused on delivering a single message. “Of course it is confused,” he wrote. “Of course it wavers between middle-class values and street values. Of

course it is not sure whether it believes in liberal pieties or militancy. Of

course some of the characters are sympathetic and others are hateful. And of

course some of the likable characters do bad things. Isn’t that the way it is

in America today? Anyone who walks into this film expecting answers is a

dreamer or a fool. But anyone who leaves the movie with more intolerance than

they walked in with wasn’t paying attention.“

“Hoop Dreams” (October 24, 1994)

Roger

and his TV reviewing partner Gene Siskel made the fortunes of this documentary

and its director Steve James in January of 1994, giving this account of two

young Chicago basketball players the top slot on their TV program the week that

it premiere at Sundance. James would later repay this gift by directing

“Life Itself.” This piece is also an example of Roger’s determination

to champion the unseen and under-appreciated. Unlike a lot of critics who had

risen to positions of prominence, one never got the sense that he was content

to review only Hollywood films or art films that had effectively been

pre-screened through the festival awards circuit. “Hoop Dreams” was

completely off-the-radar until Gene and Roger championed it.

“Deja Vu” (May 1, 1998)

Another

example of Roger sticking up for worthy underdogs in American cinema’s brutal

marketplace, this one brings together two of his recurring fascinations: with

films about people telling stories to each other (exemplified by

“Persona,” cited above, as well as “My Dinner with Andre,”

one of Roger’s favorite ’80s dramas); and with “Citizen Kane,” mentioned

here in the review’s longest paragraph, a meditation on the enduring power of

the ferry monologue from Orson Welles’s film.

“The Passion of the Christ” (February 24, 2004)

“This is the most violent film I have ever

seen,” Roger writes high up in his review of Mel Gibson’s

still-controversial Biblical drama, then goes on: “I prefer to evaluate a film on the basis of what it intends to do, not

on what I think it should have done.” Then Roger’s Roman Catholic

upbringing comes into play, giving him an insight into the film’s methodology

that other critics either didn’t have or wouldn’t bring to bear; he quotes

lines from a chant he used to say as an altar boy (At the Cross, her station

keeping/Stood the mournful Mother weeping/Close to Jesus to the last) then

warns, “This is not a sermon or a

homily, but a visualization of the central event in the Christian religion. Take

it or leave it.“

“Synecdoche, New York” (November 5, 2008)

It

is impossible to read this review of Charlie Kaufman’s directorial debut and

not think about Roger’s struggles with cancer, a disease that would ultimately

claim him less than five years later. It is personal criticism at its best,

connecting with readers on the most basic level, and in the process, reminding

us that for all its tricky formal devices and conceits, this is ultimately a

simple film about how every story is one story. “Using a neurotic theater director from upstate New York, it encompasses

every life and how it copes and fails. Think about it a little and, my god,

it’s about you. Whoever you

are. Here is how life is supposed to work. We come out of ourselves and unfold

into the world. We try to realize our desires. We fold back into ourselves, and

then we die.”

“Knowing”

(March 18, 2009)

In

some ways the inverse of Roger’s “Blue Velvet” pan, this is an

example of a critic standing up proudly on his dedicated soapbox and saying,

“Hey, everybody, listen up: that film everyone is telling you is terrible

made a big impression on me, and I believe there’s something to it.” In

this case, Roger sees a film about “the

most fundamental of all philosophical debates: Is the universe deterministic or

random? Is everything in some way preordained or does it happen by chance? If

that question sounds too abstract, wait until you see this film, which poses

it in stark terms: What if we could know in advance when the Earth will end?“

“The Spectacular Now” (August 2, 2013)

This

was one of the last reviews Roger wrote, and to my mind one of his best,

bringing to bear all the craft he’d learned in the preceding four-plus decades

as well as an unabashed optimism and love of youthful energy that he never lost

to age. “What an affecting film this

is. It respects its characters and doesn’t use them for its own shabby

purposes. How deeply we care about them.“

To donate to The Ebert Center, click here.