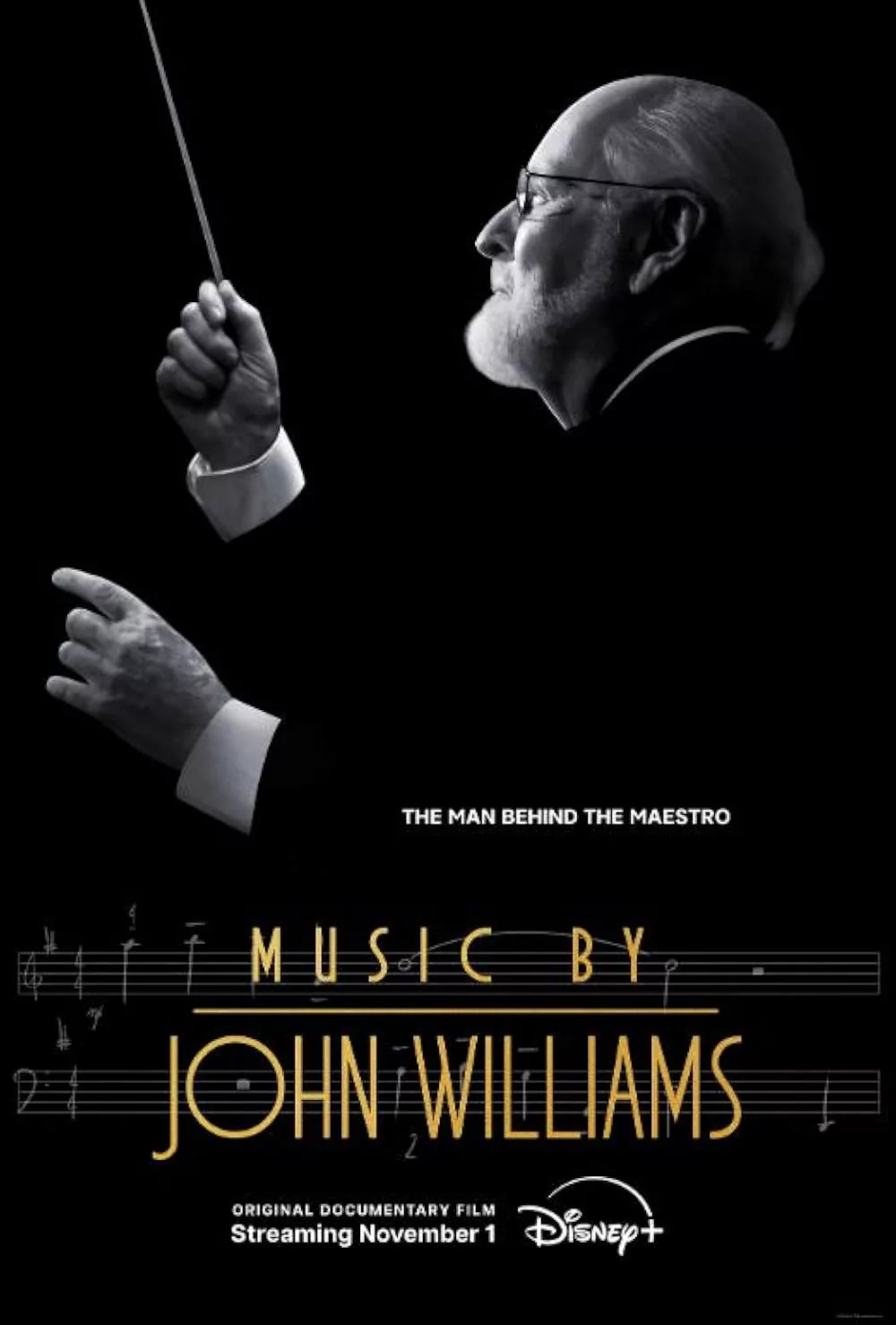

“Music by John Williams” probably would’ve been a pleasure to watch even if it hadn’t gone as deep into the process of scoring as it does: a glorified supplement, made enjoyable mainly by the way it hits our nostalgic triggers. What makes it special is that it truly cares about the nuts and bolts of marrying pictures to music and understands how to explain the finer points to people who aren’t musicians.

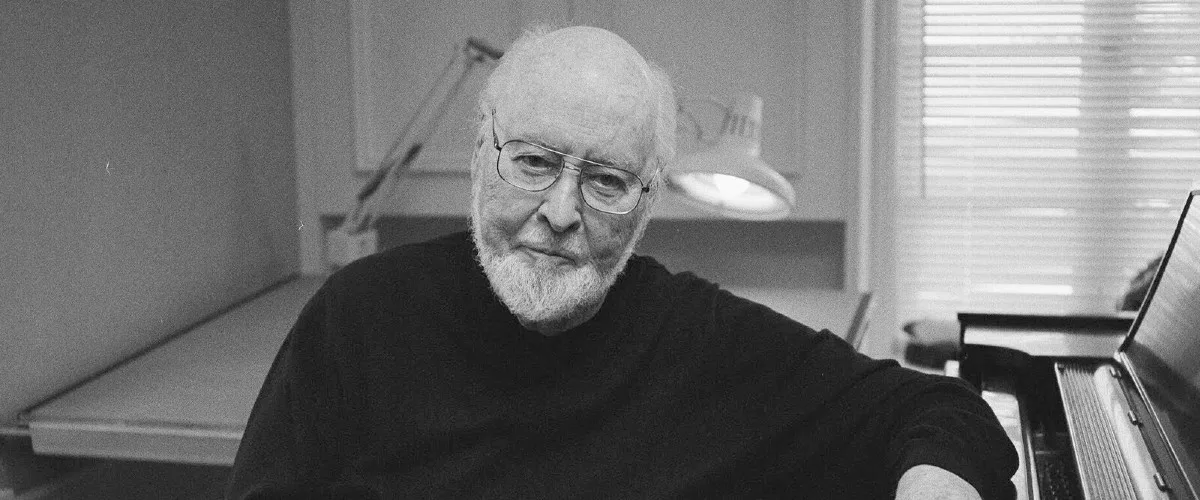

“Music by John Williams” is a Disney+ documentary directed by Laurent Bouzereau, who for many years has pretty much been the official chronicler of the careers of Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, and other major American filmmakers in their orbit. A certain comfort level is evident in the interviews with Williams, now 92, as he sits at the same piano he’s composed scores on since the 1960s and walks us through the theory and practice of his work, which stretches from TV scores in the 1960s (“Lost in Space,” incidental music for “Gilligan’s Island,” playing piano on the “Peter Gunn” theme) through the blockbusters of the 1970s (“Star Wars,” “Jaws,” “Superman” et al) and on into the 21st century (the “Harry Potter” main theme, the “Star Wars” prequels and sequels, and more Spielberg movies). Williams’ final score before retiring was Spielberg’s cinematic memoir “The Fablemans,” bringing the story of their partnership full-circle.

“Music by John Williams” is a product of, and in some sense an ad for, Disney, which absorbed Lucasfilm (which made the Indiana Jones and Star Wars films) and which, as a result of buying 20th Century Fox, now also owns Williams-scored films released by Fox, including the “Home Alone” series and movies by Robert Altman, Oliver Stone, and Chris Columbus. But it doesn’t play like a stealth informercial for a music catalog wholly owned by a media conglomerate or hedge fund, which too often the case with documentaries about musicians made recently.

And it’s never content to just let its various interview subjects—including Branford Marsalis, Elvis Mitchell, J.J. Abrams, and many other film composers, including Thomas Newman and Alan Silvestri—lavish Williams with compliments. Once the movie has gotten past its throat-clearing, too hype-y prelude (apparently mandatory in the streaming age), it settles into a relaxed and satisfying mode, somewhere between a critical biography of a major American artist and a teaching tool for anybody who wants to learn more about how movies are made. It returns to breathlessness at the end, but it feels earned, given the scope of Williams’ accomplishments.

Throughout, Bouzereau keeps the focus on the practical aspects of filmmaking and film scoring. He brings in biographical elements only when they’re important to the timeline of Williams’ development, ensuring that the film never devotes into “…and then he went here, and then he did this….” There’s detail about Williams’ relationship with his father, mother, siblings, and children, all musicians, as well as the transformative effect of losing his first wife, actress-singer Barbara Ruick, to an aneurism when she was just 43. Williams’ scores are occasionally excerpted as underscoring for biographical montages, in clever ways that connect with the subjects of the films that he composed them for (music from Spielberg’s memoir “The Fablemans” appears in the part about Williams’ youth.

Much of the documentary is anchored to Williams sitting at the piano, illuminating the art and act of film scoring. He walks us through the ideas behind some of the most artistically as well as commercially and technically significant blockbusters of the last 60 years, sometimes varying the rhythm or arrangement of famous leitmotifs to show how differently a famous sequence might’ve played if he’d changed just one or two little things.

Williams is often joined onscreen by Spielberg, his greatest collaborator and an excellent teacher/guide who’s almost as eloquent as Williams when it comes to explaining how the filmed image merges with music to create something grander than either can achieve on its own. The friendship and partnership of Williams and Spielberg is the backbone of the movie, and the source of its warmth and much of its humor, as when Williams talks about being so moved by a music-free early cut of “Schindler’s List” that he told Spielberg that he should find a better composer, and Spielberg replied, “I know, but they’re all dead.”

Just as “The Fablemans” puts a new frame around many of Spielberg’s films and gives you fresh eyes with which to see them again, “Music by John Williams” will make you want to revisit Williams’ scores and think about the connections to his life. Williams’s score for Spielberg’s “Catch Me If You Can,” for example, is not just a throwback to jazz-orchestral ‘50s and ‘60s work by Elmer Bernstein on films like “A Walk on the Wild Side” and “The Sweet Smell of Success” (Bernstein was one of many great score composers who employed the young Williams, who is credited here with the piano part for Bernstein’s “To Kill a Mockingbird” score). It’s also a callback to Williams’ own pop-jazz scores for ‘60s TV shows that he did under the name Johnny Williams. And it’s a connection to his jazzy work for Robert Altman on series TV and the movies “The Long Goodbye” and “California Split.” And it’s an affectionate, sideways tribute to his dad’s work as a jazz drummer, and to growing up around jazz players. “My parents’ friends were all musicians,” Williams says, “and that’s what I thought you did when you were an adult.”

The jazz factor also comes up in the section about the original 1977 “Star Wars,” Marsalis—who calls Williams’ piano performance on the “Peter Gunn” theme “the foundation of jazz funk”—observes, “It’s hard to imagine someone writing a piece like the cantina scene while knowing absolutely nothing about jazz. I’ve heard a lot of bad pieces like that, and it comes across as a cliched affectation at best.”

And of course the documentary is a valedictory for Williams, the last of a breed of film scorers that used to be the norm in Hollywood. Williams came up in the final decade of the old studio system in the early 1960s after honing his chops in Air Force bands. His first scoring job was a documentary about the maritime Canadian provinces. He played in studio orchestras at Columbia and 20th Century Fox under the direction of such legends as Bernard Herrmann, Henry Mancini and Franz Waxman. He composes without a computer, picking out melodies and themes on his piano and writing charts with a pencil. His grandson Ethan Gruska says, “He’s somebody who learned his skills painstakingly, and now he’s living in a time when you can conjure music from a prompt with AI.”

I learned a lot about Williams’ work (and the art form as a whole) from watching this film. It’s filled with illuminations, such as Silvestri’s comment on Williams’ minimalist piano theme for “Jaws” (“One thing a theme brilliantly can do is, it can keep a character on screen even when they’re not visible on screen”) and Williams’ analysis of the five-note theme for the aliens in “Close Encounters” (“like a conjunctive sentence or phrase that ends with and, if or but”).

At 100 minutes, “Music by John Williams” is too brief to delve into any one score for long (it could’ve been a 10-part series). A lot of work gets skipped over as a result. But that’s the nature of the beast. You can’t say everything, in words or music. Choices must be made. Still, this is an essential work not just on Williams but many of his composer peers, role models, and filmmaking partners, and on filmmaking generally. It will be watched for pleasure and taught in schools. Like a John Williams score, it lingers in the mind after the final credits have ended.