There’s a special kind of pleasure in watching a small movie by barely-known actors and filmmakers and realizing a few minutes in that you’re seeing the kind of film that launches multiple (hopefully long) careers. “I Love You Forever” was that kind of experience for me. It’s about a tight circle of twentysomething Detroiters whose navel-gazing complacency is disrupted by a bad romance between one of the young women in the group and a guy who’s everything she’s always wanted and might end up destroying her life. Incredibly, it’s a comedy. Mostly.

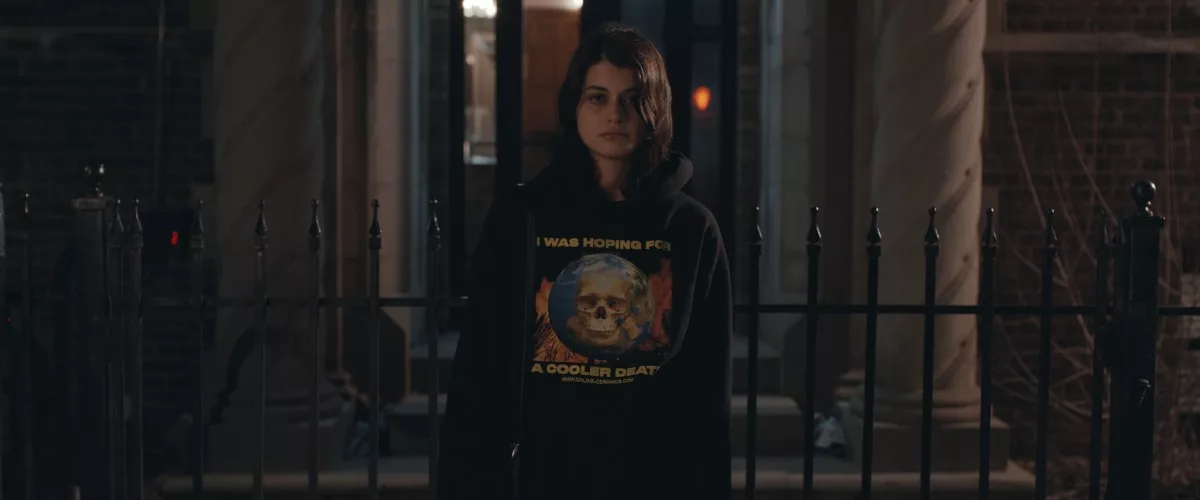

The young woman, Mackenzie (Sofia Black-D’Elia), is a hardworking law student who’s entering the final year of her studies. The young man, Finn (Ray Nicholson), is a local newscaster who meets Mackenzie at the birthday party of her best girlfriend, Abby (Cazzie David), and shows off his rare gift for flirty banter. There’s a palpable connection, so Finn gives Mackenzie his phone number and waits for her to call, then takes her to the most romantic dinner of her life, jump-starting a love story for the ages.

Or at least it feels that way to Mackenzie. Her already low standards for men were degraded over the years by her regular hookup Jake (Raymond Cham Jr.). Jake is selfish, thoughtless, uninvested in Mackenzie except when they’re having sex, and uninterested in commitment. Ally calls him “a human vape pen.” But that doesn’t stop Mackenzie from pathetically wishing he could be her boyfriend anyway.

When Finn sweeps her off her feet, she finally gets what she always wanted: a man who lavishes her with attention and affection and makes her feel like she’s the center of his universe. But it’s a “monkey’s paw” sort of fulfillment. Finn is a little monster of neediness, and his initial presentation as a dashing, semi-famous prince darkens into something more troubling. He’s a stone in her shoe that she can’t get rid of, and that gets bigger and sharper. Finn is passive-aggressive and sometimes just aggressive in his neediness. His smothering, demanding meltdowns make it hard to focus on any other important part of her life (including school) because she’s constantly on edge. Even in class or at a gathering of friends, she finds herself zoning out and glancing anxiously at her phone. She’s expecting a text from Finn that’ll require her immediate attention and keep hold of it for hours or days, and knows it’ll appear when it’s least convenient.

“I Love You Forever” isn’t a true-crime or case study sort of movie, the type that starts with sunshine and rainbows and ends up with the leading lady in a grave, a shelter, a hospital, or a courtroom. It’s a level-headed portrait of a more everyday sort of misery: a relationship that becomes low-key hellish pretty early on and keeps getting incrementally worse. Finn never lays a hand on Mackenzie in anger. But he does whine and yell and manipulate and sometimes smash things or burst into tears. Is he tormented by undiagnosed mental illness? The movie doesn’t say so, but we wonder.

Mackenzie knows she ought to break up with Finn but won’t, or can’t. Why? It’s inferred that she’s needed romantic attention for so long that she’d rather have the bad kind than none. She’s also a self-punishing person who blames herself for making Finn act this way, and believes, against all evidence, that he can be saved, or can save himself.

I’ve concentrated on the more intense and troubling elements of the story. But I don’t want to give the impression that “I Love You Forever” is a dire slog, because it’s not. The most remarkable thing about is the way it shifts gracefully between explosive and often tearful confrontations, wordless psychological insights into characters as they sit and think about what’s happening to them, and cutting, often knowingly satirical dialogue that pushes the characters to the brink of cartoonishness (“If you’re not gonna do therapy, can you at least look at the Tik Toks I sent you?”). Then, it suddenly backs away from the edge and restores their warmth and dimensionality—or reminds you of how singularly weird and special they are in spite of it all. (In one scene, Ally brings her curling iron with her to a sidewalk brunch and explains, “I didn’t want to spend the entire day worrying if I left it on at home”).

The cast is uniformly excellent, even in the smallest roles. Their performances merge with the observant writing to create a portrait of a specific time, place, and demographic. Most of the movie is dialogue-driven, but the moments when the movie shifts into a more impressionistic mode—often by focusing on characters’ faces as they react to what’s happening in front of them or contemplate their present situation—it showcases a gift for subjective filmmaking that’s as undeniable as its gift for talk.

The movie starts to repeat itself in the second half, and ends rather abruptly, with what feels like a stab at a bleakly comic punchline but might make you wonder how much deeper the story could’ve gone if it had devoted less time to Finn and Mackenzie’s downward spiral and more to Mackenzie’s reaction to having endured it. As a showcase for young American talent, it’s tough to beat. At its best, it reminded me of a rougher, more glassy-eyed 21st-century version of the kinds of movies Whit Stillman—and later, Noah Baumbach—have made. There, the characters initially seem like verbose, privileged, self-absorbed twits but you care about them anyway. After all, their delusions are relatable, even if their lives aren’t.