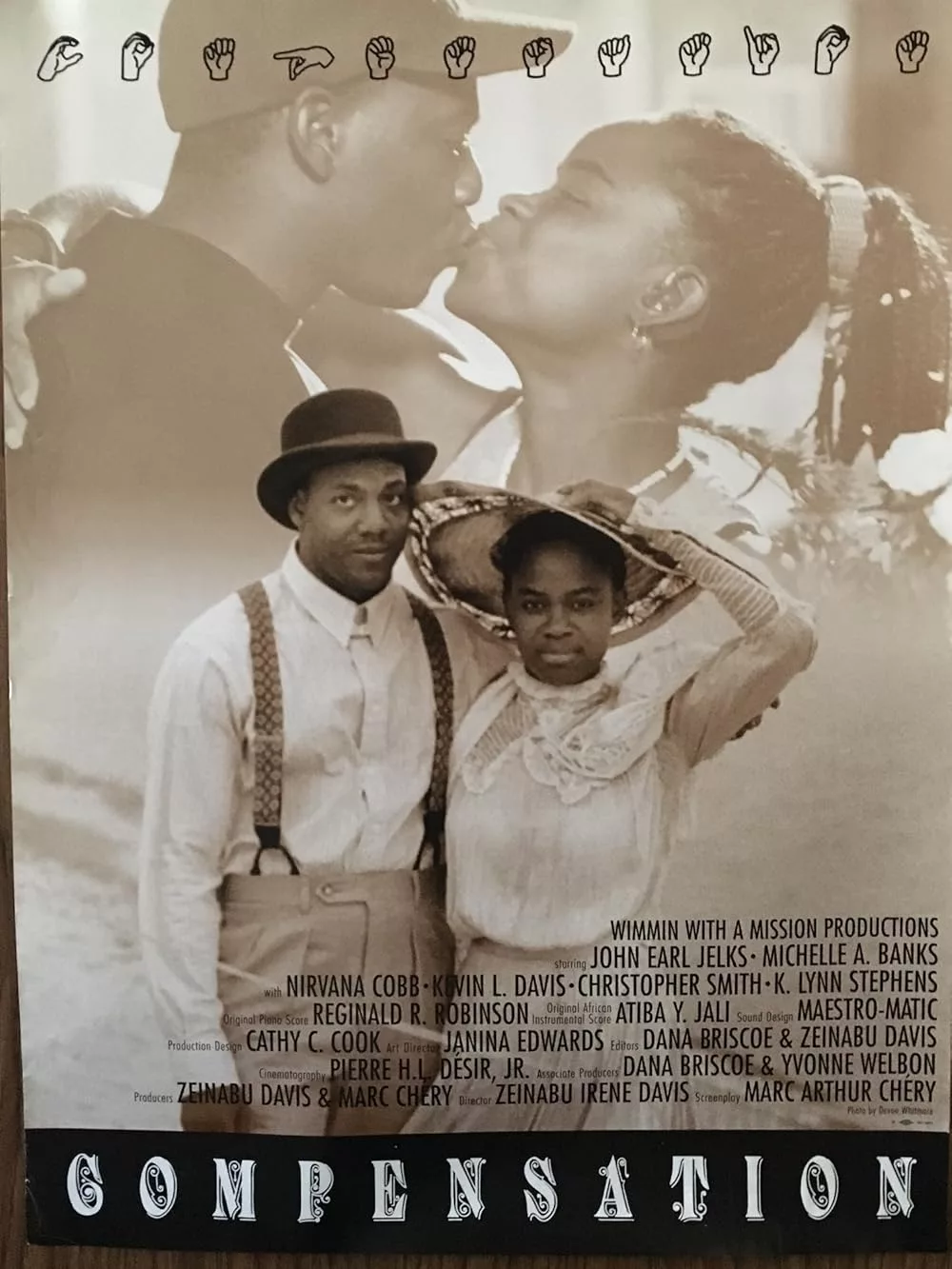

“Compensation,” director Zeinabu irene Davis’ masterpiece, is a film guided by the desire to represent facets of Black life and history left relatively unexplored. Based on the eponymous Paul Laurence Dunbar poem by screenwriter Marc Arthur Chéry (Davis’ husband), the film is a romance set across decades and shared by reincarnated amorous spirits.

One half of the film takes place in 1910 Chicago, between Deaf educator and seamstress Malindy Brown (Michelle A Banks) and Southern migrant Arthur Jones (John Earl Jelks). The other half occurs in the early 1990s, between Deaf artist Malaika Brown (Banks) and librarian Nico Jones (Jelks). Heartbreaking circumstances and unlikely chance define each relationship, and Davis’ visionary approach—which imagines deafness and Black life in infinitely gentle terms—spellbindingly brings us into a soulful world.

Much like love in “Compensation,” it took time for Davis’ exciting film to return. Part of the LA Rebellion—the film movement that produced Charles Burnett, Billy Woodberry, Julie Dash, and more—Davis had already directed several rich films: “Cycles” (1989) and “A Powerful Thang” (1991)—before making “Compensation.” Premiering in 1999 at the Atlanta Film Festival, “Compensation” would also eventually garner Independent Spirit Award nominations.

Unfortunately, like several other contemporaneous films directed by Black women: “Drylongso,” “Alma’s Rainbow,” “Naked Acts,” etc—”Compensation” soon faded into obscurity until experiencing a recent resurgence that’s inspired a 4K “rejuvenation,” as Davis calls it, carried out by The Criterion Collection and The UCLA Film and Television Archive. In its return to theaters, we’re reminded that “Compensation” was far ahead of its time.

Its unique vision is evident early on. Intertitles rendered like a silent film provide a brisk rundown of the era: Chicago’s “colored population” doubled between 1900 and 1910, W. E. B. Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folk was published in 1903, and The Chicago Defender began printing in 1905. Archival black and white photos show Chicago as a bustling metropolis bursting with crowds, horses, street cars, and trains. Further photos of affluent Black people and Black migrants traveling from the south, whose faces Davis’ piercing camera pushes in on to imbue these historical photos with a dynamic effect, give viewers an idea of the era’s cross-section of class.

What also sticks out is the expanded open captioning (Davis collaborated with “The Tuba Thieves” director Alison O’Daniel to update this component), whose placement around the frame and whose specificity: “pace of piano quickens,” “distant whistles”—firmly plants viewers in a fast-moving, exponentially growing city brimming with potentiality and inequality.

In this evolving setting, Malindy, described via an intertitle as “a woman of much talent and ample learning,” builds out this world. Though she comes from wealth, she is not insulated from the era’s racism: She attended the Kendall School for the Deaf until it became segregated in 1906. She worships at Calvary Baptist Church, where many of the newly arriving Black folks not only find spiritual guidance but also intermingle with the already-established Black families in Chicago. She is also a Deaf person whose pronounced movement isn’t obscured by Davis. We read her journaling (the intertitle has a hand and pencil in the lower-right-hand corner), using a chalkboard to communicate with hearing people and teaching American Sign Language (ASL) to others. We also see her find love during her initially awkward meet-cute with Arthur on a wind-swept beach, him carrying a mandolin as big as his heart. “I do not speak like you,” Malinda writes on her chalkboard. “I can’t read, miss,” Arthur dejectedly responds.

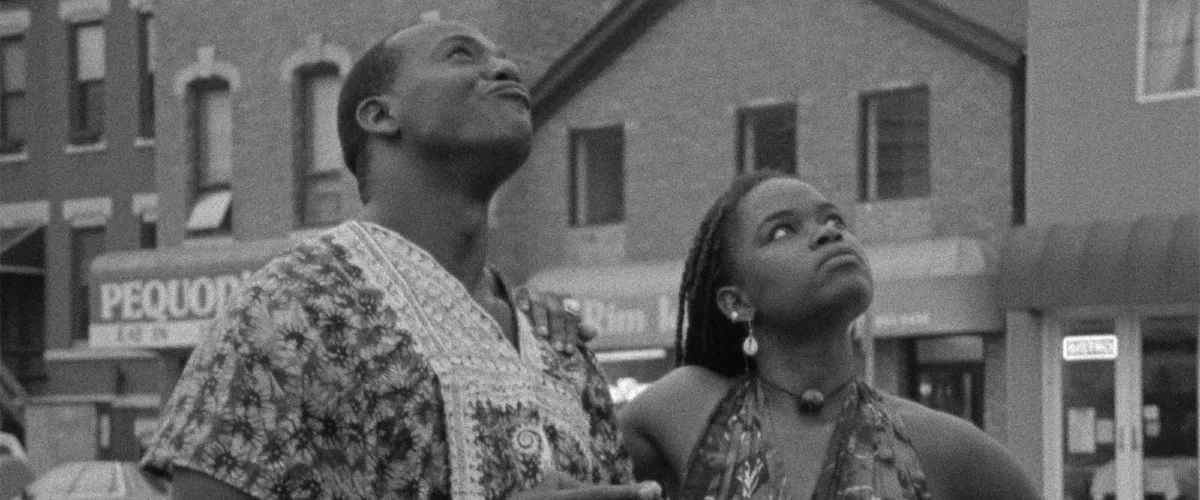

Decades later, Nico and Malaika have a similar meet-cute. Malaika meditates on the beach; her serene visage stops a jogging Nico in his tracks. He tries to work some game, which allows for a hilarious inner-monologue exchange. “The silent treatment,” a buffoonish Nico thinks. “This brother ain’t got no good sense,” a cutting Malaika says to herself. Unlike Arthur and Malinda, whose relationship is predicated on Malinda finding possibility in Arthur despite his education and class, Nico must have the initiative to leap into Malaika’s world.

“Compensation” is a film about spaces. Nico and Malaika visit Deaf clubs and bars and go to the movies. Arthur and Malindy also attend the movies, watching a fictional comedy short, “The Railroad Porter,” that reminds viewers that Black people have been attending and acting in films since the dawn of cinema. The activities in the modern setting, therefore, rethink the romantic comedy. On the other hand, the romance in the period setting acts as a living text for a kind of critical fabulation that fills in the realities of Black life that have been erased.

By seeing Davis’ inventive handling of the sumptuous wonder that is “Compensation,” the blow of this film being her lone dramatic feature is immeasurable. Through these two relationships, she manages to confront the HIV/AIDs epidemic and Deaf civil rights while maintaining a blithe energy that pulls African folklore and song for a rich gumbo of influences. She also pushes her aesthetic language, stacking open captioning and leaning on double exposures to heighten tension and allow space for avant-garde dance to occur. She also explores Chicago with intense curiosity, settling in neighborhoods like Rogers Park that are not often included in other movies, infatuated by the city’s skyline.

Most of all, Davis inspires two incredible performances by Banks and Jelks, two giving actors whose charisma and chemistry are as intoxicating as any strong brew. Davis has a knack for highlighting human characters, fallible people working through trials in the pursuit of love. Maybe that’s why the film’s most indelible image, Nico and Malaika holding each other, is so powerful. Because in their embrace, Black love conquers time.