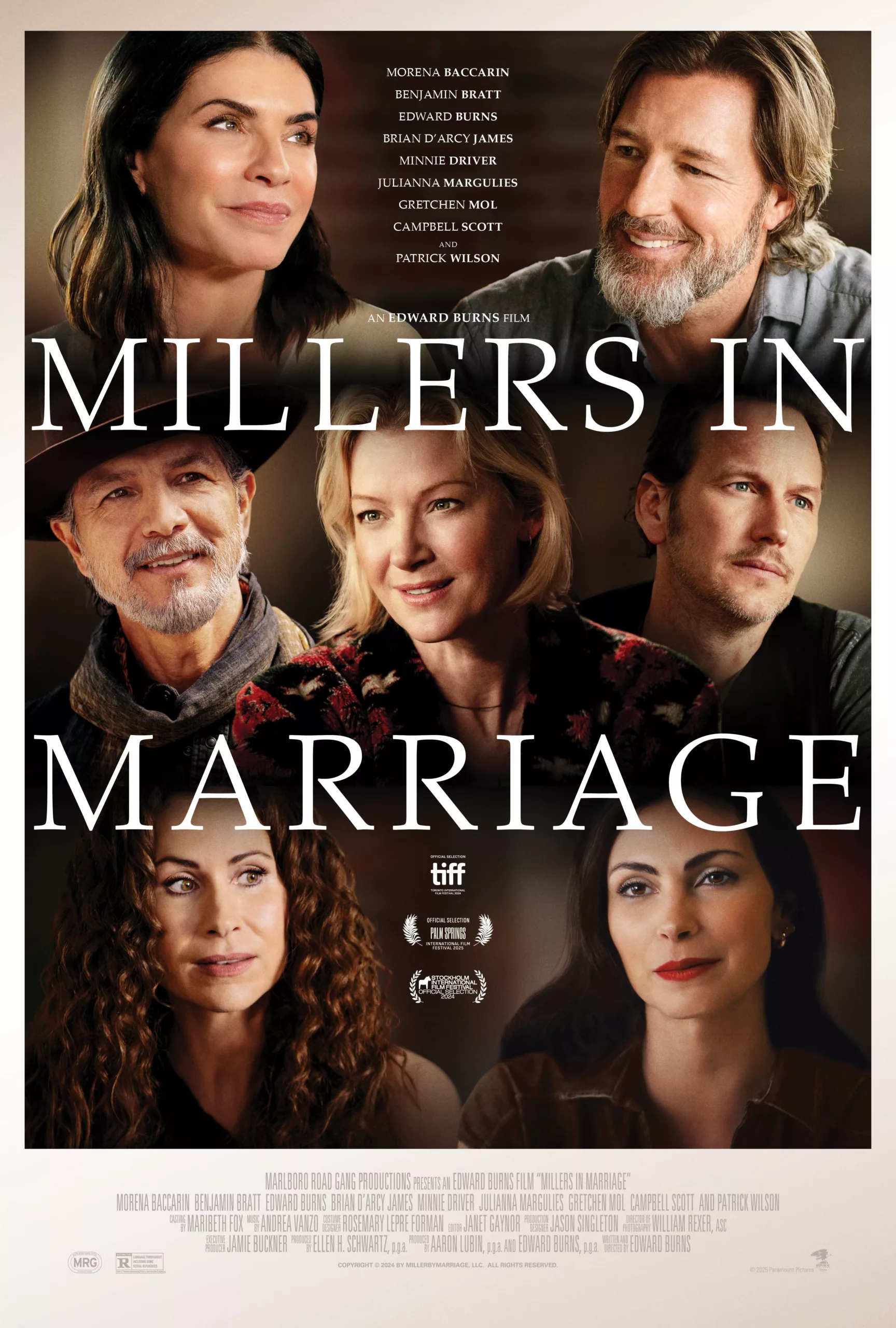

“Millers in Marriage” isn’t a science fiction movie. Which is unfortunate, because if it were, we might’ve gotten a decent explanation for why one minute of the characters’ lives makes you feel as if you’ve aged a month.

Written and directed by Ed Burns, the movie looks and feels a bit like one of those French movies that used to be a common sight in American art house theaters—the kind where very well-off characters deal with problems such as infidelity, professional envy, unrequited love, and creative ruts, in kitchens that are the size of most people’s entire apartments. Nobody is a bitter old professor with a much younger wife who was once his teaching assistant—a standby in “relationship movies” aimed at the donor class in other countries as well as in France.

But aside from that, it has all of the other hallmarks, including an ensemble cast that’s thick with writers and musicians who have second homes in the country and a solo piano score (by Andrea Vanzo) that suggests depths of melancholy that the story itself only occasionally achieves. One character critiques another character’s novel-in-progress by admitting that, although it’s good, it’s definitely part of the subcategory “rich people and their champagne problems.” This is the movie being self-aware.

The anchoring characters are the Millers: Two sisters and a brother. The brother, Andy Miller, is an accomplished painter. Andy is played by Ed Burns, who has long hair and a greying beard and is only shown painting one time, so you kinda have to take everyone’s word for it that he’s a painter. Andy was recently divorced by his fashion executive wife Tina (Morena Baccarin) and has started seeing Tina’s colleague Renee (Minnie Driver), but Tina’s already jealous and has started snooping and skulking around and making noises like she wants to get back together, or at least ruin whatever Andy’s trying to build.

One of Andy’s sisters, Maggie (Julianna Margulies), is a very successful novelist whose somewhat older husband Nick (Campbell Scott) apparently had some early success but has been blocked in recent years. Nick is now feeling envious of his wife’s popular touch (apparently he works in a more “literary” vein, and halfheartedly tries not be snobbish about it) and also obsessing over her seeming disinterest in their union, as well as the possibility that she’s staying in the marriage mainly out of habit and to gather raw material for her work. In the upstate community where Maggie and Nick have a house, a handyman and rental property manager named Dennis (Brian D’Arcy James) who has bedded a lot of local women presents himself as a potential romantic alternative for Maggie, or at least a fling. She interested and says she’s not wired for monogamy and states that she and Nick have an open marriage, but falls suspiciously silent when asked if Nick (who sarcastically describes Dennis as “a playa”) is on board with the arrangement.

There’s one scene where we hear a snippet of a book that one of them (Maggie) wrote. But otherwise, here, as with Andy’s painting, the art that these characters’ lives revolve around is trotted out more as a signifier of sophistication and social class, as opposed to the prism they see the world through, much less a skill or profession they have to work at. Ditto Andy’s other sister, Eve (Gretchen Mol), a one-time indie singer-songwriter who gave up her art when she got married and pregnant and is missing it now that her wealthy, alcoholic husband Scott (Patrick Wilson) is spending lots of time in other cities without calling or texting her. Scott is a a colon blockage in human form: a sexist bully and an embarrassing, angry drunk who is shown destroying their teenage son’s piano rehearsal for music school by staggering in an hour after its scheduled time, berating Eve for not waiting for him even longer, and demanding that the young man start over. Eve suspects that Scott is cheating on her. The opportunity presents itself for Eve to cheat on Scott with a music profile writer named Johnny, who had a crush on her during her indie stardom days in the ’90s and unsuccessfully tried to pick her up (Johnny is played by Benjamin Bratt, who’s ten times more charming than the movie deserves).

There’s a scene where we see Eve working on a new song, her first in many years, jotting down lyrics on paper with a pencil. It’s both a lovely work-in-progress and a charming moment of performance by the seemingly ageless, endlessly likable Mol. But here, again, we kinda have to take the characters’ words for it that they do the things the movie says they do. They could just as easily be in entirely different, non-arts related professions for all the difference it makes in the movie’s presentation and execution. If a filmmaker is not genuinely interested in the lives of artists, why not just say, “They all inherited a lot of money from their rich parents and don’t have to work if they don’t feel like it” and move on to the infidelities and heartbreaks, which is where the movie’s interest lies? Only Scott, a manager whose business is about money, seems a plausible candidate to have acquired the lifestyle that’s being depicted. (If you’re thinking that artists are treated so poorly in this stage of American capitalism that the only way they could live comfortably in New York City and have this much apparent leisure time is to be born rich, you’re not wrong; but that’s a subject for another piece.)

Burns was always a serviceable director whose screenwriting largely consisted of characters telling you what they were feeling, and announcing what they were about to do or once did, as opposed to, well, actually talking, in a naturalistic or stylized manner (either is fine when done well), employing subtext and accidental foreshadowing and indirection and other fancy stuff. (Sample dialogue: “You know how I turned 42 last week, and last month we celebrated our fifteenth wedding anniversary?”)

The writing has gotten more sophisticated only in the sense that the stories are now unfolding in a moneyed world that’s probably a lot like the one Ed Burns inhabits at this point in his career: the sort of milieu where owning multiple, gorgeous domiciles in a costly part of the country is considered unremarkable, and everybody’s life is so handsome, organized, and clean that you have to assume they have a lot of paid helpers. There are a few thoughtful moments of characterization and dialogue, as when Johnny toasts Eve with, “Here’s to the pleasures that failed to last, and the dreams that didn’t come true,” and seems to think he’s being ruefully wise but is actually destroying any chance he might’ve had at getting lucky that night. But they’re meteors in a fixed sky.

But Burns has grown a bit as a director. His style is more spare and exact than it was in the ’90s when his debut “The Brothers McMullen” won Sundance, in what amounted to a consensus second choice elevated to a winner by deadlock (jury head Samuel L. Jackson described it diplomatically as a movie that they could all agree on). He parlayed that into a series of low- to medium-budget indies where he seemed to be auditioning to become the working-class, outer-borough New York answer to Woody Allen or Claude Lelouch. William Rexer’s handsome but not ostentatiously pretty, straight-to-the-point medium shots and close-ups add a lot in this regard. But the camera is employed mainly as a recording device here, rather than as an expressive tool: a way to record performances and plot. “Millers in Marriage” is a movie, but it’s not cinematic. It could have been a stage play, though not one that it’s easy to imagine a reputable company producing unless a lot of famous and semi-famous actors’ names were attached.

The word “privileged” is overused, but it applies here in a big way. The problem with this movie is not that the characters are comfortable. The problem is that none of them seem to realize how comfortable they are, and the movie rarely does, either, even in a subterranean, ironic sort of way. Nobody’s gaze seems to extend beyond the edges of their own navel, which by default forms the outermost border of the movie’s vision of life.