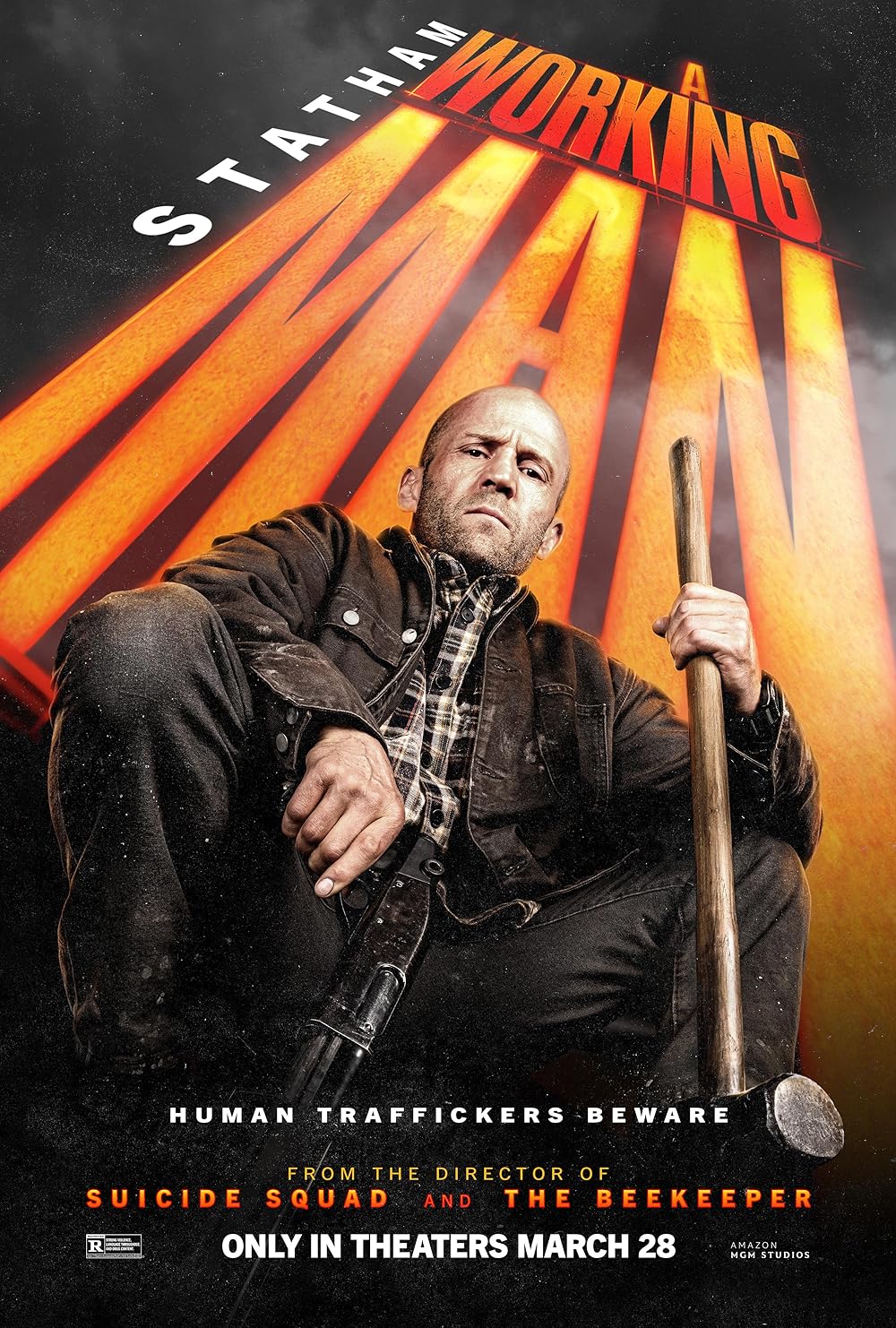

If you’re going into “A Working Man,” the latest Jason Statham action flick, then you know that whatever it’s supposedly about is basically incidental. You also shouldn’t expect any sense of realism or immersive character work. I joked with a few people before my screening started that Statham doesn’t have to choose whether to employ an American accent or not. His accent is simply “Statham.” One could say the same about his movies. They brazenly trade in genre conceits to the point that accusing his action flicks of pilfering from “John Wick” or any Michael Bay joint feels like missing the forest for the 2×4 that’s heading straight for your jaw.

Because the ability to take the best pieces of the genre, in the process making your own specific brand of action movie, to the point that your name becomes a kind of trademark, is paramount for an action star. Statham has done it. You can only judge Statham’s work on the scale he’s built for himself.

Nothing surprising happens in “A Working Man,” his second collaboration with David Ayer following the entertainingly outlandish assassin-revenge movie “The Beekeeper.” Like that film, Statham plays a badass in quiet hibernation. Here, he’s Levon Cade, a construction foreman for a company owned by an empathetic Joe Garcia (Michael Peña). On this site, no one cares about his military past, a tragic backstory that’s delivered in an animated montage that at one point features a cement truck whose mixer is shaped like a grenade. His quiet life, however, is interrupted when Joe’s daughter, Jenny (Arianna Rivas), is kidnapped by human traffickers employed by a Russian mobster. Though Joe offers him a small fortune to recover Jenny, for Levon, this is a matter of principle. He promised Jenny he’d always have her back. And he’s not about to break his word.

Going any deeper into the film’s overloaded plot is probably a fool’s errand, but here are a couple of other notes. Levon is a widower who retired from the army in the hopes of gaining custody of his precocious daughter Merry (Isla Gie) from his bitter father-in-law. That fatherly spirit serves as an additional reason he wants to reunite Jenny with Joe. Following the “John Wick” method of world building, the Russian mobsters here aren’t your run-of-the-mill underworld kingpins. They possess their own secret bylaws, powerful networks, and complex internal workings—like an on-hand cleaning service for disposal of bodies. While Levon stashes his daughter for safekeeping and works to find Jenny, these mobsters conduct their own investigation to figure out why Levon is hunting them.

These subplots, which seemingly only exist to tease a potential sequel, take a backseat because in reality Statham is the plot. Sure, Levon goes through the motions of searching for Jenny, some torturing here, some subterfuge there, but when he discovers his target, a wayward Russian playboy named Dimi (Maximilian Osinski), there isn’t any narrative tension to the standard-issue script adapted from Chuck Dixon’s novel Levon’s Case by Sylvester Stallone and Ayer. This is simply a vehicle for Statham to inflict some on-screen damage.

Statham, for his part, doesn’t disappoint. Levon makes a room in a downtown flophouse his base of operations. He tortures a Russian baddie in a luxe mansion and infiltrates a road house located in the middle of nowhere, where he engages in a stomp fest soundtracked to Dropkick Murphys’ “The Boys are Back.” When Levon is finished smashing skulls and breaking elbows, Dutch (Chidi Ajufo), the road house’s boss, shakes Levon’s hand and with his whole chest exclaims, “Look at them bricks! You’re not a cop. You’re a working man.”

That silly one-liner isn’t strictly for applause. It also hints at the film’s hopeful audience. See, fewer and fewer films are set in the Midwest, and even less of them feature what might be termed a “blue-collar hero.” And while there aren’t exactly deep political themes here, Statham certainly isn’t leading a class revolution, it’s significant seeing Statham, ironically a Brit, out there portraying a larger-than-life “American” worker fighting against Russian influences.

Though Statham delivers his end, Ayer’s visual language is a mess. The lighting in about half the shots are backlit and overblown within an inch of the laws of physics. The film, set in Chicago, features more inserts of the city’s skyline than lines of dialogue. Despite the constant tips of the cap to Chicago, the film also lacks a sense of place. Why is the wind whipping up a storm in one nighttime sequence? Well, this is the Windy City, right? I’m also usually not a stickler for a movie making geographical sense when venturing across a city’s grid—you shoot what locations you can, when and where you can—but if you’re aware of Chicago’s look and feel, Ayer’s editing will throw you for a loop. How does William go from a residential neighborhood to the heart of downtown to Joliet’s woodland surroundings? It’s a bit of movie magic, whose constant switching from urban to rural in service of a mob land story often recalls another Chicago action film “Next of Kin.”

Still, it’s clear that Ayer ultimately understands why people watch Statham’s movies. On top of his rugged and bruising fighting style, the deadpan one-liners, the nonsensical plotting, and, now, an everyman heroism are what makes Statham action’s few top-of-the-marquee stars. Even when there’s a comically large moon that feels ripped from a Méliès movie undercutting whatever emotional drama Ayer wants to pull in the film’s climactic raid on a brothel, it doesn’t matter. Because if “The Meg,” “Wrath of Man” or “The Beekeeper” proved anything, it’s that it doesn’t matter how outlandish or overcooked the movie is. Nothing can slow down Statham.