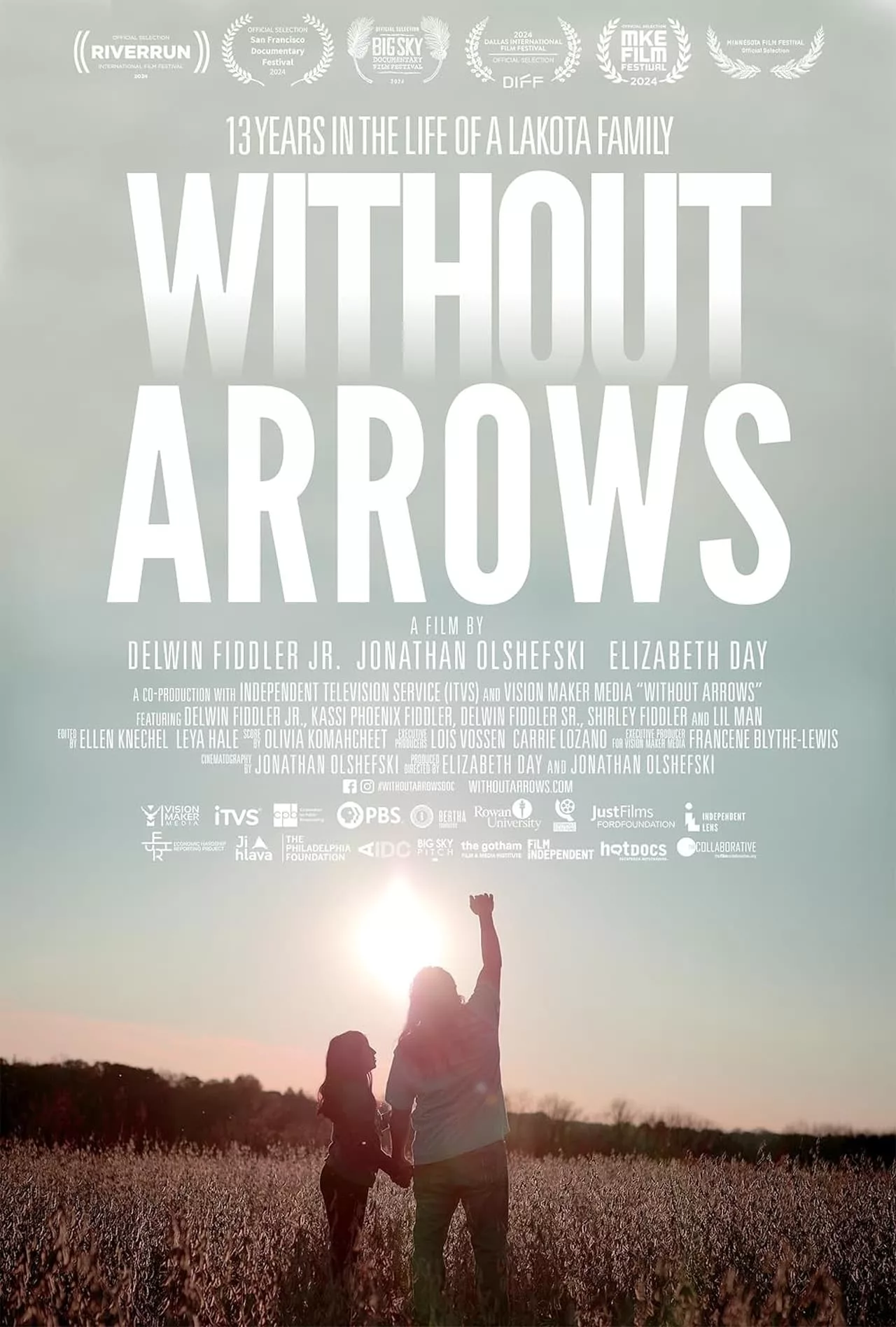

“Without Arrows” is an ironic title for a film that pierces the heart. It’s a loving portrait of a damaged but unbowed way of life, that of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe. That makes it important for archival reasons. But what makes it art is the way it uses the language of cinema to capture the experiences of life as it is lived, decade after decade; and also as it is recalled in present tense: as a series of images and moments, including ones that might have seemed unremarkable when they were happening, and that spark melancholy reveries when we realize we didn’t appreciate them at the time. It’s compact—90 minutes, plus credits—but it feels layered and dense. Its scope is astonishing for a movie that carries itself so modestly.

Shot over a span of 13 years, starting in 2011, the movie chronicles the life of Delwin Elk Bear Fiddler, a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe and a Native American performing artist. The story begins when Delwin decides to leave his adopted home of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to return to the place where he grew up, the Cheyenne River Sioux tribe reservation in South Dakota. Reconnecting with his mother, father, siblings and friends inspires him to stick close to the place. The tribe is succumbing to the assimilationist din of the society that militarily shattered them, then culturally and economically imprisoned them. If any remnant of their ways is to survive, somebody in the community is going to have to take on the burdens of remembering and transmitting.

But as John Lennon sang, life is what happens to you when you’re busy making other plans. “Without Arrows” ends up being a portrait of a Native American artist who responds to a calling but encounters great resistance as he tries to answer it. He struggles to reconcile his urge to create his own art and identity, apart from his family and culture, and the sense of responsibility he feels towards them. The former pulls him away from his ancestral home. The latter keeps pulling him back.

The story is expressed in a fragmented series of mini-movies, each set in a span of weeks or months. The individual scenes and shots have been edited together (by Ellen Knechel and Leya Hale) with a flowing, montage-like rhythm suggestive of Terrence Malick, whose films (like this movie) seem to give almost equal weight to the struggles of individuals and the beauty and sometimes harshness of the natural landscapes that frame their stories. (Be warned that the film contains brief images of livestock being cut up for food.)

It’s moving to watch Fiddler try his best to maintain a straight line of measurable progress leading to a goal (to help preserve and extend the cultural identity passed down to him) even as he’s constantly getting diverted, slowed, and sometimes halted by life itself, which doesn’t care about our agendas. He gets older, thicker, and grayer. He becomes a devoted father to a daughter and bonds with her by teaching and passing down his artistry. He struggles to earn a living as an artist and reluctantly embraces day jobs. You see him getting beaten down a little more each year. His determination to keep his chin up is a form of heroism that movies rarely depict, much less celebrate.

Sadly, inevitably, as time flows onward, he loses people he loves. Some losses are shocking, others preordained. They all sting. You know going in that his mother and father are getting up there in age, and also that they smoke and don’t generally take care of themselves. About halfway through the movie, after seeing Fiddler’s parents get older and sicker and more mobility impaired, you begin to dread the inevitable losses before they arrive, which is one of the many qualities of this movie that makes it feel so tough and real.

Fiddler comes across as an everyman, representative not just of his tribe or Native Americans generally, but humanity itself. He’s a working-class hero who’s doing the best he can in an economy that treats workers like livestock to be rendered and consumed. There’s a soft-spoken nobility in the way he keeps trudging forward through life, doing what he has to do to care for his family while finding ways to continue nurturing the art that means so much to him.

Fiddler is one of three credited co-directors of “Without Arrows,” along with Jonathan Olshefski, who began chronicling Fiddler’s experiences after becoming friends with him in Philadelphia; and filmmaker Elizabeth Day, a member of the Ojibwe nation from Minnesota who Olshefksi invited to collaborate and ensure accurate representation. So this is a group effort, composed of material gathered over a long time span—longer than the production of Richard Linklater’s “Boyhood,” which was a sort of fiction-documentary hybrid about the impact of time on life. (I’d love to see the two programmed as a double feature.)

By the end of “Without Arrows,” I started to hear a song playing faintly in my mind, as if on a loop: “Some Other Time,” from the musical “On the Town.” “Where has the time all gone to?” it asks. “Haven’t done half the things we want to. Oh, well—we’ll catch up some other time. There’s so much more embracing still to be done, but time is racing.” The song strikes so deep because we all know that, where our loved ones are concerned, we keep promising to catch up with them properly but rarely do, and then they’re gone; and also because at some point, hopefully a long time from now, we will catch up with them, in another way.