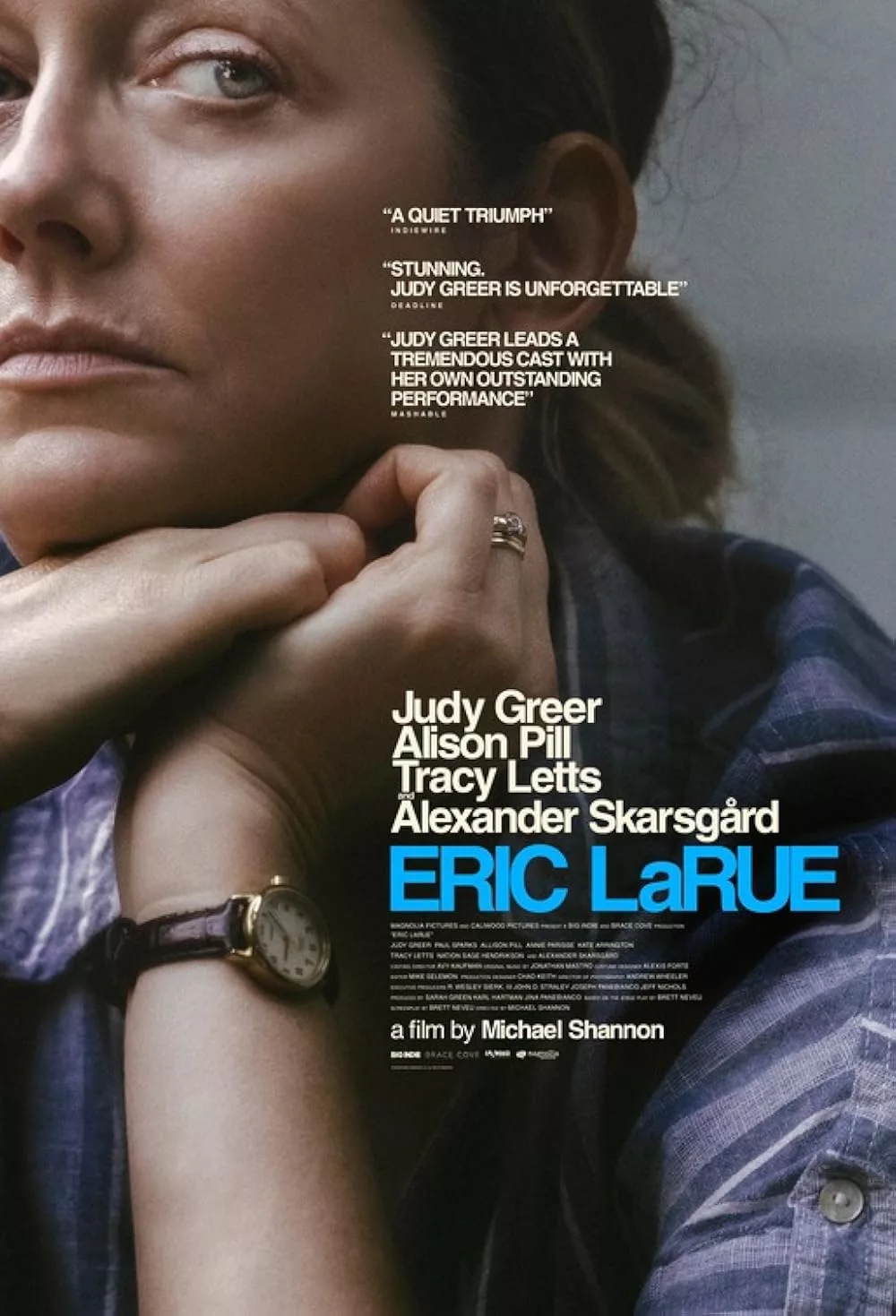

Chicago’s Red Orchid Theatre, founded by Michael Shannon, Guy Van Swearingen, and Lawrence Grimm, has been in operation since 1993. They put on a couple of plays a year, both original works and established classics. Chicago is such a vital city for theatre, and Michael Shannon’s directorial debut, “Eric LaRue,” comes directly out of that tradition. Written by Red Orchid ensemble member Brett Neveu, the play had its world premiere back in 2002 (a production which I saw; along with a number of other mid-late ’90s Red Orchid productions).

“Eric LaRue” shows the aftermath of a school shooting as experienced by the shooter’s parents. Neveu is interested in the inadequacy of two religious leaders in the community, attempting to help their parishioners make sense of the tragedy. Judy Greer and Alexander Skarsgård play Janice and Ron LaRue, whose son Eric (Nation Sage Henrikson, not seen until the penultimate scene in the film) shot three kids at his school. Eric is now in prison, and Janice and Ron are still reeling, trying to find their footing in this new horrible landscape.

Janice is practically housebound. It’s been a year, and she hasn’t gone to see her son in prison yet. She sits on the couch and stares at his closed bedroom door. There’s humiliation and denial: she has no idea where he got the guns, and she wants to know who, as though that will shift some of the blame. The pastor at her church, an awkward “cheerful” Steve Calhan (Paul Sparks), attempts to engage her in conversation at the grocery store. You can see he is trying, and you can see the pressure he feels—as a religious “leader”—to be there for his flock. He’s not a crisis counselor, though. He’s just a guy, and he has no idea what he is doing. Meanwhile, Ron has started going to another church, a more hardcore church with the encouragement of a colleague (Alison Pill, superb) whose bright smile barely masks the gleaming fanaticism of a zealot.

Ron starts talking about how he wishes his wife would accept Jesus. He tells her, “You will have immediate peace!” She replies, “I don’t want immediate peace.” Pastor Calhan’s attempt to facilitate “healing” between Janice and two of the victims’ mothers (Kate Arrington and Annie Parisse) does not go according to his plan. The other mothers don’t want to hear about how hard it’s been for Janice. Things are tense. Calhan keeps trying to control how they express themselves. He tries to shut down any sign of anger: “That’s not what this is about!” he cries. Maybe he imagined tearful hugs, and everyone would feel better. You have to pity him. He’s doing his best, and his best is not good at all. Ron’s pastor (Tracy Letts) is a much stronger leader.

The cast is made up of Shannon’s long-time colleagues, including Letts, who wrote both Killer Joe and Bug, in which Shannon starred. Arrington is not only Shannon’s wife but also a Steppenwolf Ensemble member and a theatre veteran. Parisse is married to Calhan. These are all heavy-hitting actors, and the scenes have tremendous intensity—the kind of intensity when pain and rage are so immense that the characters fear to express them at all. No wonder someone like Ron finds refuge in a controlling environment where grief and shame are bypassed, as long as you are “saved”. Janice can’t find refuge at all. Greer is the center of every scene, and she has absorbed the pain and shame and humiliation, the sense of being stopped up by the “inappropriate”-ness of her own feelings. Nobody’s going to hold a candlelight vigil for her son. Nobody will cluster around her saying, “I’m so sorry.”

Shannon’s approach is uncompromising but not heavy-handed. He hasn’t watered down the material. The style is unfussy but distinct enough to give the film a dissociated quality. The color is drained from the screen. The background is sometimes almost entirely blurred out, evocative of the self-centeredness of grief. Only you and your pain are in focus. The rest of the world is a blur. When we finally meet Eric he both is and is not what we expected. The scene is so well-written that I rewound it to watch it again.

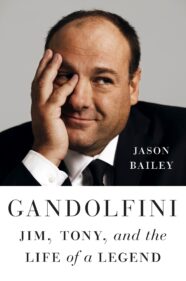

In 1999, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold rocked American life (but not enough, clearly) by going on a shooting rampage through their high school in Columbine, Colorado. Neveu’s play, written soon after, was an attempt to understand and process what had happened. Much focus in the media was put on the killers (trenchcoats, Marilyn Manson, diaries), but imagining the event through the eyes of the parents was new. Since then, multiple works of art have attempted it. “We Need to Talk About Kevin” (Lionel Shiver’s book and the 2011 film adaptation) is told from the perspective of the mother of a kid who killed classmates with a crossbow. In 2019, Sue Klebold, Dylan’s mother, shared her experiences in the documentary “American Tragedy.” 2021’s “Mass” shows the parents of a school shooter sitting down with the parents of a victim and attempting to communicate. The fourth episode of Netflix’s “Adolescence” shows the family of a 13-year-old killer attempting to go on with their lives. “Eric LaRue” predates these works by one or two decades. If nobody wants to hear about Sue Klebold’s suffering in 2019, then nobody really wanted to hear about it in 2002.

The questions at play are ones that the wider public often doesn’t want to ask. The killers generally come from good, middle-class families. (As Eminem snarks in his song “White America,” also released in 2002: “Middle America. Now it’s a tragedy. Now it’s so sad to see.”) Whatever the shooter’s parents go through, grief that their son did this, grief that their son is now dead or in prison, it is not permissible to discuss. They must grieve alone, all while experiencing nonstop harassment. It’s rich territory for storytelling.

The final shot of “Eric LaRue” is ambiguous, and silence surrounds it, even as the music begins and the credits roll. Pastor Calhan tells the three women in his office, “You are going to come through to the other side of this, and everything’s going to be better.” Nobody says anything; nobody looks relieved; nobody even appears to be on board with what he said. Uneasiness flicks at the corner of his smile, and he adds, “Do you believe me?” Even he doesn’t believe what he’s saying.