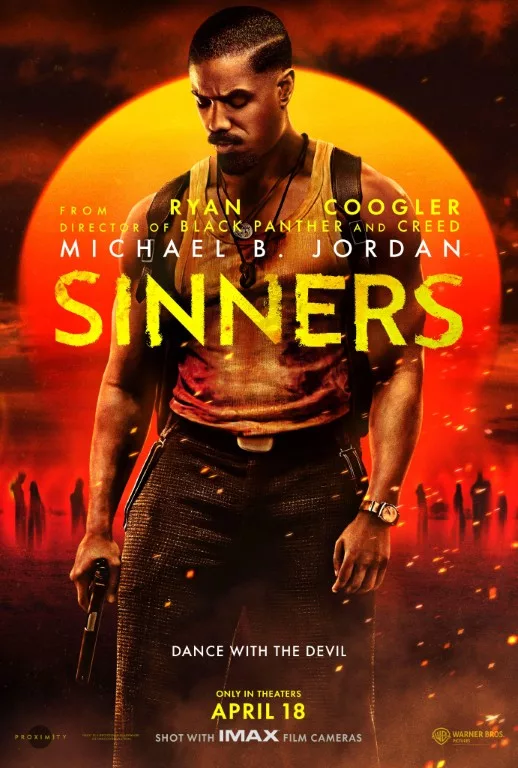

Vampire movies often struggle to be inventive. The formulas and mythologies of the subgenre are tried and tested, repeated and reworded: Stinging holy water, foul garlic, burning sunrises, and firm wooden stakes through the heart are the primary tools wielded against the undead. Oftentimes, the biggest change from story to story is merely the setting, whether it’s a far flung Eastern-European country, an American urban locale, or a stifling desert. Knowing those limitations, I have to give “Sinners,” a sweaty, gory Southern Gothic horror musical, some credit. It’s a messy picture that throws the kitchen sink at the genre and, yet, somehow, often misses.

In Ryan Coogler’s “Sinners,” Michael B. Jordan plays Smoke and Stack, bootlegging brothers and former soldiers who left home long ago to fight in World War I before settling in Chicago to work for Capone’s outfit. They’re returning to the Mississippi Delta with rolls of cash and cases of Irish beer to open a juke joint in a disused sawmill bought off a racist white man, and they hope their little cousin Sammie (Miles Caton, a former backup singer for H.E.R. who mostly holds his own) will help them out. Despite their best plans, however, they’re unable to create a safe space that’ll protect attendees from the Jim Crow racism present in 1932. A bloodthirsty company will visit them before their lone day of business is out, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

“Sinners” is a Coogler movie through and through, attempting much of what the writer/director tried to accomplish with “Black Panther: Wakanda Forever.” The director reaches for epic scope when intimacy would do just fine, mourns broken Black lineages, and makes bare the stains of American racism. It also returns Jordan to the fold in a dual performance that attempts to be smoldering and desirable, imposing and heroic. It’s a shame to see Coogler’s ambitious designs ultimately conform to genre conventions, causing the intended awe to happen only in flashes.

The cast, a diverse assortment of major talents that takes a while to assemble, illustrates the film’s broad scope. “Sinners” briefly opens with a scarred and disheveled Sammie, brandishing the severed neck of his guitar, arriving back at his father’s white church, desperately searching for salvation. The film then flashes back a full day, picking up with Smoke and Stack’s arrival in town. We then follow their hiring of local talent: the alcoholic bluesman Delta Slim (a wonderfully slippery Delroy Lindo) for entertainment, a Hoodoo conjurer named Annie (Wunmi Mosaku) to cook food, Grace (Li Jun Li) and Bo Chow (Yao) to mind the bar, and Cornbread (Omar Benson Miller) to guard the door. Former flames, like Stack’s past lover Mary (Hailee Steinfeld), who many mistake for white, also arrive. As does Pearline (Jayme Lawson), a local girl with whom Sammie is smitten. The accumulation of characters and backstories takes long enough that we don’t arrive at the juke joint until about an hour into the film.

Coogler intentionally takes his time because he wants to narratively and visually immerse you in this world. He often leans on elaborate oners, extended by whip pans to take viewers, for instance, from Bo Chow’s shop on one side of the main street to Grace Chow’s, which is located on the other. He holds shots, allowing your eyes to travel across Smoke and Stack’s resplendent suits or to catch the sweat that rolls under the Southern sun. Coogler proudly shot on 65mm with IMAX cameras, hoping to harness the large scale and aesthetic information the format offers. While the choice provides moments of unwavering, textured beauty, its tendency to create a shallow focus, thereby blurring the background, makes the characters appear separate from an environment integral to their lived reality. Why set a film in the South if the endless cotton fields, the bent trees, and even the life teeming around these characters will be held at a visual distance? The same can be said for the high contrast and deep shadows of Coogler’s compositions, which fit the film’s horror tone but shroud Jordan’s face, often, in his most emotionally heightened scenes. Even some of the cuts appear slightly off schedule, as though Coogler is furiously trying to spool the film before it jumbles in front of him.

The film’s topics, which are equally disordered, are varied and inseparable from Coogler’s career: African folklore, America’s racial history, decimated Black families, Black freedom, Black-owned properties, the importance of ancestors and kin, and the binding power of music. Sammie is the nexus for many of these themes. A preacher’s son and talented Blues guitarist, he possesses the uncommon artistic strength to link eras and segments of the diaspora just by strumming. In one of the film’s most electric scenes, Sammie yowls so fervently to the juke joint’s parishioners of sharecroppers, his music becomes a phantasmagoria of African drummers, an Afrofuturist electric guitarist, and even Chinese dancers. Coogler’s camera spins and twirls through this maze of colors and sounds for a vibrant cacophony that spells the rapturous boundaries he could push if he didn’t have to turn around and figure out the vampire component of his movie.

The film’s final freakout is a deliciously gory affair instigated by Sammie’s otherworldly music. Drawn by Sammie’s uncommon abilities, three white vampires singing Irish folk songs saunter up to the juke joint, where they ask for entry. Though initially rebuffed by Smoke and Stack, and without spoiling much, their ultimate way in feels like Coogler warning against the dangers of whiteness in spaces built for people of color. The consequences of crossing such color lines, therefore, result in a gruesome tableau, where composer Ludwig Göransson’s twangy score downshifts into growling metal and the aspect ratio expands to accommodate every spilt speck of blood. This collision of “Queen of the Damned” and “From Dusk Till Dawn” offers plenty of spectacle, even if it offers few new wrinkles to the vampire mythology, especially as it relates to the film’s Southern setting.

Even if Coogler doesn’t know where to end his movie, it’s tempting to be swept up in his expansive vision, if only because his intent is so firm. Still, I often wondered who this movie is about. Is this Smoke and Stack’s story or Sammie’s? The final three scenes, including a mid and post-credit scene, play more like box checking. Jordan is the star, so he needs a final big scene where he goes full Rambo. We need to know what happens to Sammie, so there must be an explainer scene. Also, we need to leave the audience at peace, so let’s make another sequence for that purpose, too. The inability to end on a specific note mutes the impact of the previous attempts, making for a film that spins out of control. However, on a landscape afraid to grant directors the freedom to take massive swings, especially for Black filmmakers like Coogler who’ve earned the right for such big statements, making a movie that feels too big is a sin worth forgiving.