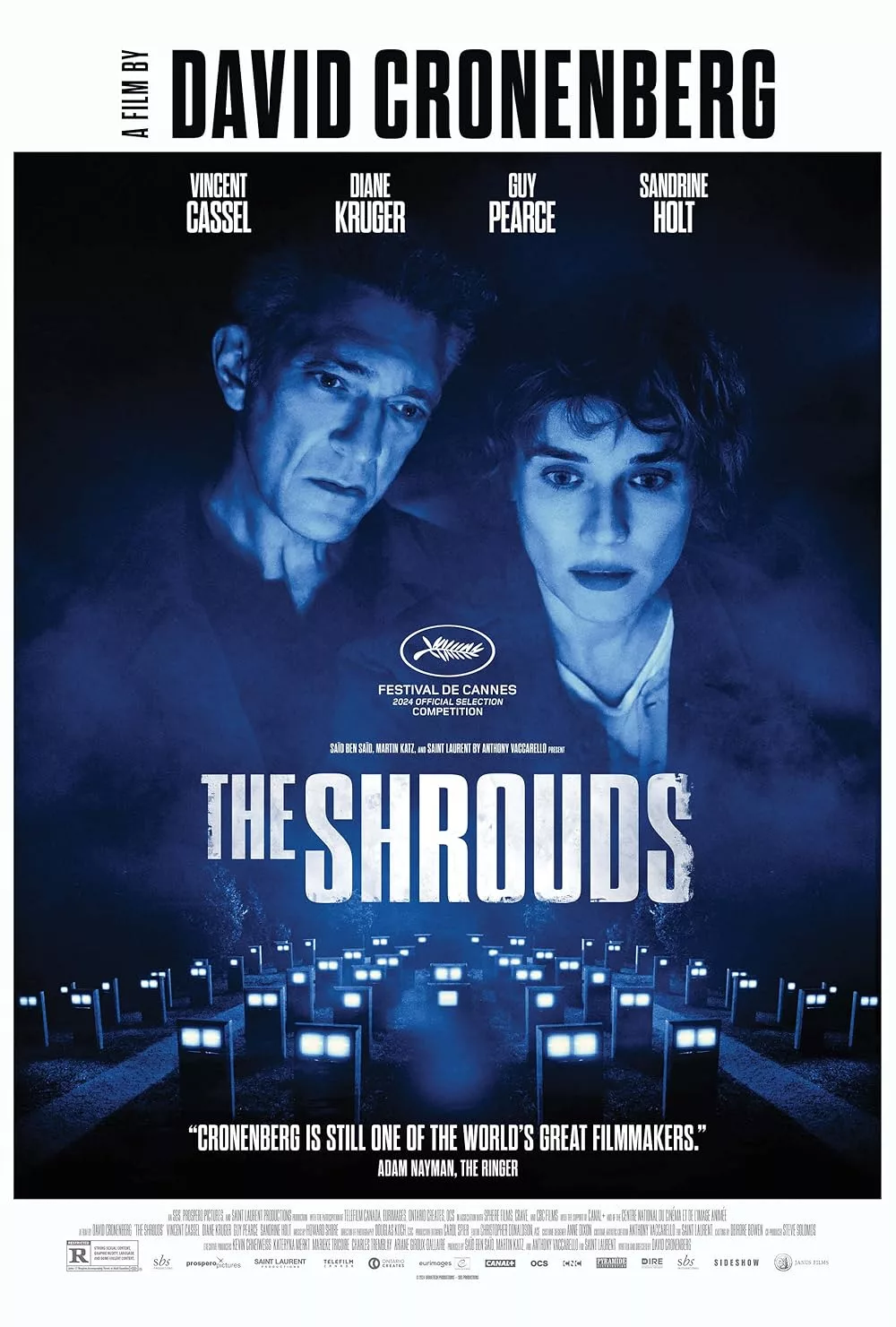

David Cronenberg has been making movies for fifty years. His themes and images have stayed so consistent that his filmography spawned not one but two indispensable bits of terminology. One is “Cronenbergian,” which, like its cousin “Lynchian” (after David), describes a very specific cinematic vibe that is most efficiently communicated by naming the artist who perfected it. The other term is “body horror,” a subcategory of horror about the fragility, poetry, and malleability of the flesh, and our fear of its integrity being violated. “The Shrouds,” about a widower who deals with his grief by creating a new kind of cemetery where the living can observe the decay of their loved ones’ bodies, is a Cronenbergian body horror of integrity and force.

The movie owes its existence to a real-life body horror that Cronenberg experienced when his wife of 43 years, Carolyn, was diagnosed with a cancer that ravaged her body and ultimately took her life. It’s very much a “late Cronenberg” film in the vein of “Cosmopolis,” “Maps to the Stars” and “Crimes of the Future,” in that its primary form of screen action is conversation, and its blocking, composition and overall approach to narrative and characterization owe as much to theater and television as cinema. (It was originally supposed to be a Netflix series, but after Cronenberg wrote two episodes, the streamer canceled the project.)

Most of the action revolves around four characters. The central character is Karsh (Vincent Cassel), who channeled his unending grief over his wife’s death by inventing GraveTech, an Internet-wired graveyard/mausoleum that lets customers watch the gradual decay of their interred loved ones through an encrypted (“pun intended,” grins Karsh) iPhone app.

Diane Kruger plays multiple roles. She’s Karsh’s late wife, Becca, who appears in scenes that feel more like hallucinations or dreams (parables, even) than typical flashbacks; and she’s Becca’s only sibling, Terry, a veterinarian turned dog groomer who witnesses his journey through grief while dealing with her own. The fourth major character is Terry’s ex-husband Maury (Guy Pearce), a digital guru who both Karsh and Terry describe as a “nebbish” and a “schmuck” but has a particular set of skills that once proved useful to Karsh, and could again. Among his many contributions, Maury created Hunny, a digital assistant who helps Karsh in daily life and listens to his problems–and often seems to be flirting with him, though subtly enough that Karsh usually overlooks it. (Kruger is the voice of Hunny as well; what a hall of mirrors!)

The inciting incident in “The Shrouds” is the targeted destruction of seven markers on the grounds of GraveTech by an unknown person or persons. Cronenberg builds this out into a murky conspiracy that might involve international financiers and Russian and Chinese influences, and that partially erases and rewrites itself each time it is discussed. The movie ends on an ambiguous (or maybe just unresolved?) note that will likely annoy viewers who aren’t Cronenberg aficionados, but only if they stick around long enough to see it—and they may not. “The Shrouds” is more a play of ideas than a straightforward horror movie. There’s no shortage of gore, medical wounds/scars, amputations, and other disturbing images (and sounds). But a lot of it consists of Karsh puzzling his way through the conspiracy, such as it is, and the devastating personal loss/obsession that plunged him into it.

Still, beware the tendency to approach each new film as a product to be evaluated and rated like a washing machine or gaming console. It ill-serves art in general, but especially art like “The Shrouds,” where the core of the work is so private, personal, and raw that describing it in terms of what “works” or “doesn’t work” amounts to a refusal to truly engage. Or, to put it even more frankly: I am keenly aware of everything that has been said against “The Shrouds” as a movie, even specifically as a Cronenberg movie, and I may even agree with some of it; but at the same time, I don’t care, because I don’t think any of that stuff matters as much as what “The Shrouds” is doing that no other film has done before.

What do I mean by that? A lot of things, but for starters: Despite the movie’s darkly fantastical imagery—or because of it?—”The Shrouds” seems to me a more ruthlessly honest treatment of what terminal cancer does to the body and soul of its victims and their survivors than most “realistic” films dare attempt. For that reason alone, it should be seen by anyone who lost a significant other to this scourge of a disease. Sigmund Freud knew that sex and death were entwined at every level of human experience. That principle has been illustrated throughout Cronenberg’s filmography. But it’s been placed before us here with singular nerve and bluntness.

There are no lens-flared shots of lovers frolicking on a beach in better times. There are no sweet-tearful statements of eternal devotion delivered by glamorous stars whose characters are coded as “cancer patients” because they have a wrap around their hairless head, a morphine drip in their arm, and a smidgen of pale makeup to suggest “sickness,” but not enough to gross out a viewer who has no experience with cancer or just doesn’t want to see what it actually does to the body.

The movie begins with a husband’s nightmare of his late wife’s naked body decomposing in a grave and gets grimmer and stranger from there. Even in films and TV programs where a woman loses a breast to cancer, they don’t usually show you what the chest looks like afterward. Here, they show you. Several times. They also let us hear Karsh talking about how his unending desire for his wife conflicted with the knowledge that cancer was hollowing out her bones, and sex might break something.

“They’re chopping away at you,” Karsh tells Becca, in one of many figurative-seeming conversations where they’re both naked in their marriage bed and we see the damage done to the once immaculate body that Karsh worshipped like a shrine. We live in an era of popular culture in which, as RS Benedict’s classic essay put it, “Everyone is Beautiful and No One is Horny,” but Cronenberg has remained a proud outlier. Deep into the Marvel era he has continued to make R-rated science fiction dramas for thinking adults, with loads of sex and nudity in addition to all the other aspects that make them unsuitable for children.

Still, the carnality is interwoven so closely with his thematic preoccupations and psychological insights that to call such scenes “unjustified” is a confession of media illiteracy. Every intimate scene in this movie matters, and has a rare power to disturb because it cuts through Karsh’s dashing but chilly intellectuality, revealing him as a hopeless romantic; and tests our complacency as audience members about what’s acceptable to show in a motion picture.

Karsh’s soul was eaten up in tandem with his mate’s body. He may perhaps have devised GraveTech as a way to give himself permission to live forever inside that dreadful emotional space in the guise of studying it or offering others a way to process it or master it, rather than trying to integrate it into what came afterward, then evolve and progress to some other state. What looks like progress to him, or at least movement, could be a coded version of stasis. Or not? There’s no oversimplification here, no bromides, no self-help, no answers; just exploration and talking, and images that have that characteristically Cronenbergian fusion of horniness, sadness, intellectual restlessness, and curiosity about how far both the characters and the movie can go.

What Karsh describes as “the injection of technology into the bosom of Mother Earth” marks this as another Cronenberg movie that is essentially a modern riff on “Frankenstein,” but with infusions of eroticism, romantic obsession, and aching loss that are more John Keats than Mary Shelley. There are also trace elements of Cronenberg’s “Dead Ringers” (kind of a quasi-incestuous platonic love story about identical twins bonding through their surgical practice and their debauched private lives) and Alfred Hitchcock’s “Vertigo,” about a man who becomes obsessed with a woman who looks exactly like a great love who was cruelly taken from him. Karsh’s most vulnerable insights are offered to Terry, who looks enough like Becca to be thought of as her twin. Terry listens to Karsh with nonjudgmental fascination and increasing arousal. Their bonding stirs something deep. The ensuing relationship is transgressive on multiple levels and thrilling for that reason. It’s primordial, Biblical: a mutual reaching out.

The movie would make a fascinating double-feature with Cronenberg’s “The Fly,” a tragic love story about a brilliant man’s hubristic attempt to use science to transcend the limitations of the flesh, only to attain an unholy fusion of flesh, metal, circuitry, and a computerized facsimile of intelligence. As the hallowed, beloved body is incrementally destroyed or dismantled by a ruthless transformational condition (gene-splicing in “The Fly,” cancer here), the characters wonder how much of their love is bound up in the physically familiar, and whether it can transcend the decay that accompanies disease, and time itself. All of the electronic screens in “The Shrouds” are another indication of that desperate wish to transcend, whether they let a GraveTech subscriber feel as if they’re next to their beloved, experiencing their reunification with eternity, or convince a successful businessman that the fawning bot with the pert blond head is something more than a program.

“You’re afraid to be destroyed and recreated, aren’t you?” the scientist in “The Fly” rants when the fly genes multiplying inside him start to corrode his brain. He’s going insane even as he speaks his truth. “I’ll bet you think that you woke me up about the flesh, don’t you?” he continues. “But you only know society’s straight line about the flesh. You can’t penetrate beyond society’s sick, gray fear of the flesh! Drink deep or taste not the plasma spring, see what I’m saying? And I’m not just talking about sex and penetration, I’m talking about penetration beyond the veil of the flesh!” Beyond the veil of the flesh lies “The Shrouds.”