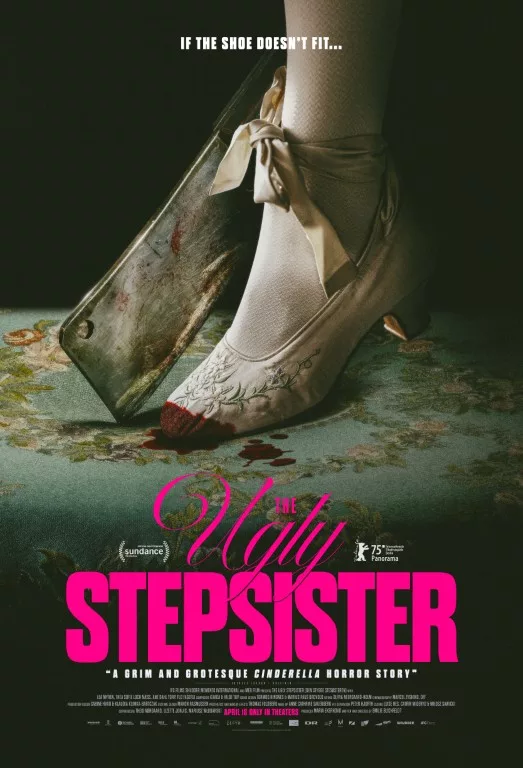

Inner beauty has no place in “The Ugly Stepsister,” a bloody re-telling of the Cinderella story from Norwegian writer-director Emilie Blichfeldt, where Elvira (Lea Myren), one of the ugly stepsisters, is at the center of the action, with the Cinderella figure her main rival. The obsession with outer beauty is a society-wide madness in the film, but no one goes further in the pursuit of beauty than Elvira. “The Ugly Stepsister” announces how far it will go early on, when Elvira pops a zit on her nose, complete with extreme closeup of the zit’s “contents.” “Extreme” is a mild word for Blichfeldt’s approach. The film includes maggots, broken teeth, a broken nose, an “Un Chien Andalou”-style optometry procedure, chopped-off body parts, and, finally, a tapeworm. What price beauty? Blichfeldt revels in the grotesque and gory, pushing things to their limit, with an unmistakable sense of glee. Lea Myren is her partner in this. Her wild, unrestrained performance is crucial to exploring the ridiculous absurdities on display.

Fairy tales sometimes serve a didactic purpose, but for the most part, they are subjective expressions of humanity’s shared collective fears. The world is a dangerous, capricious place. People are capable of horrors. Predators stalk the land, and everyone is at risk. You have no control over what happens to you. The Disneyfied version of Cinderella involves a magical fairy godmother who organizes Cinderella’s transformation, and at the end, the wicked stepsisters beg forgiveness and end up marrying well themselves. The Brothers Grimm version is not so cozy. The stepsisters cut off parts of their feet so the slipper would fit, and at the end of the story, Cinderella’s doves peck out the sisters’ eyeballs, rendering them blind. Elements of this much nastier story vibrate through Blichfeldt’s version.

The film opens with the widow Rebekka (Ane Dahl Torp) moving to the kingdom of Swedlandia with her two daughters, Elvira and Alma (Flo Fagerli), to marry a wealthy man. His daughter Agnes (Thea Sofie Loch Naess) is the clear Cinderella in this scenario, a casually pretty blonde girl, and a stark contrast to the geeky, dreamy Elvira, with her mouth full of braces. When it turns out the wealthy man wasn’t wealthy at all, Rebekka is determined that Elvira will marry well. The Prince (Isac Calmroth) is holding a ball, where he will choose his wife from the kingdom’s virgins. Rebekka gets to work. Elvira must be made over in order to attract him. So begins Elvira’s horror. Her nose is broken and reset. Her braces are ripped off. Fake eyelashes are stitched to her eyelids. She swallows a tapeworm egg to keep her weight down.

Throughout, Elvira is hopeful and starry-eyed, falling into reveries where the Prince carries her up the stairs in a swirl of wedded bliss. She has wanted to marry the Prince forever. She believes these improvements will help her chances. Each procedure is gorier than the last. Alarming gurgling sounds come from her stomach, usually at inappropriate moments. You’re not sure how that tapeworm will come out of her, but you know it will. She stashes half-eaten cinnamon buns and sweets in her drawers, wolfing them down in secret. Her hair starts to fall out. Rebekka fits her with a huge blonde wig.

Blichtfield worked with cinematographer Marcel Zyskind to create a very specific look and feel, almost Gothic in its environment and atmosphere, alongside the more magical scenery of sunlight, forests, castles, and glens. Alma and Elvira ride horses through the woods, and it looks like an engraving in a 19th-century edition of Grimm’s fairy tales. Manon Rasmussen’s costumes are absolutely stunning, the heavy satins of the skirts standing out from the waist, with different colored sashes and thick clusters of roses stitched onto the bodices. Moving through the shadowy interiors, the girls look like they’ve stepped out of a medieval tapestry. Rebekka is sinister and glamorous in her widow’s weeds, and Agnes is beautiful in her simple clothing and head scarf, by contrast. Alongside all this beauty is the grotesque and the macabre, all of the instruments of Elvira’s torture: a giant curved needle, a hatchet, the little brass covering she wears over her broken nose.

“The Ugly Stepsister” isn’t about embracing your inner beauty or discovering self-empowerment by learning you don’t need a man. It’s way too extreme for any message, and too extreme to be a cautionary tale. Even when the blandly handsome, boring Prince looks at Elvira and says he would never sleep “with that”, Elvira doesn’t falter. She submits to whatever the evil Rebekka has in store for her. Alma has somehow escaped the overriding cult-like belief in artificial beauty. She is the only character who looks around her and seems to be thinking, “Is it me, or is this behavior totally insane?”

“The Ugly Stepsister” makes its points, and then makes them again and again, creating a sense of repetition without progression. It’s not breaking news that our beauty-obsessed culture is damaging to young girls’ self-esteem. “The Substance” is an obvious comparison, but “The Ugly Stepsister” is nastier, angrier, and grosser, if you can believe it. Blichfieldt’s “burn it all down” approach creates turbulence and upset while walking over very well-trod ground.