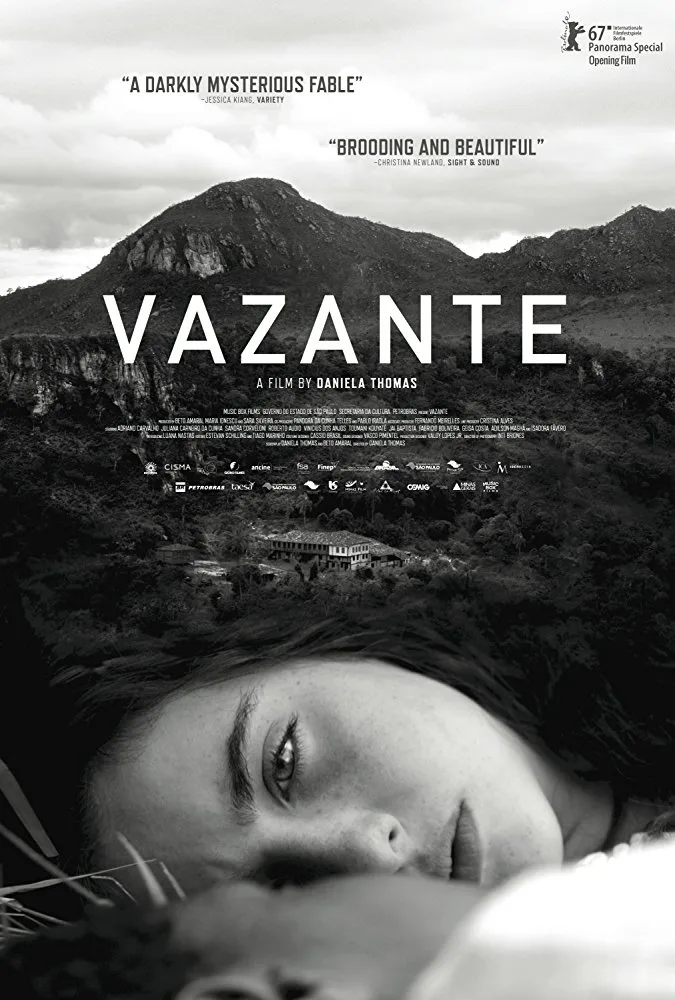

The Brazilian filmmaker Daniela Thomas is a longtime collaborator of Walter Salles, whose “Central Station” and “The Motorcycle Diaries” made international splashes in the early 2000s. Salles is a socially conscious filmmaker who, at his best, can be a cinematic spellbinder, casting beguiling moods from the screen. Thomas seems, with “Vazante,” to be more invested in atmosphere and mood than statement, at least early into “Vazante,” a film set in the early decades of the 19th century.

In Brazil, as in the United States, slaves were kept by landowners during this time. Shot in silvery black and white, the movie opens with shots of water flowing down a stream, and then cuts to a scene of childbirth. A slave woman encourages her white mistress to push. But the flow of life is not continued; the woman dies in childbirth, as does the infant.

The cattle man Antonio returns home from a trip, with lots of baby clothes, and is greeted with heartbreak. A series of complications finds him working with slaves who are more used to diamond mining than farming. There are language barriers, and an African-born slave manager who’s not above torturing his own people to keep them in line. Antonio seems in a bit of a haze, which is understandable. But his life isn’t all confusion and stumbling. He marries a barely teenage girl, Beatriz (Luana Nastas) and sets about trying to conceive another heir.

With his deep, sad eyes, Adriano Carvalho makes Antonio look a bit like a tragic hero at first. Sure, he’s a white oppressor, but he’s only fulfilling his part in a system he doesn’t control. As it happens, the movie hardly believes this surmise to be the case, but takes its time making its true point of view known.

The languidly-paced picture has a staggering array of beautiful images and vistas. (The cinematographer is Inti Briones, who also shot the striking 2011 film “The Loneliest Planet.”) Shots of a line of horsemen making their way slowly, horizontally, over a path on the side of a cliff face are epic, almost stirring. But this saga is not a triumphant one in any way. “Nothing grows here. Nothing. The only thing blacks on this farm know is mining gems,” Jeremias, the slave manager, says to Antonio about midway through the film.

The movie’s finale is a shocker, but it’s in a certain tradition. If you remember the movie version of “Ragtime,” made in 1981, it calls to mind that film’s treatment of the police commissioner Rhinelander Waldo. Played by a crusty but avuncular James Cagney in one of his final film roles, he seems like a good man in a bad situation, but at a crucial moment, he shows his true colors. That work and this work make the same statement: that regardless of how sympathetic a person committing racist acts might be, committing those acts makes him or her a vital cog in the system that they would otherwise claim to be powerless to resist. “Vazante” translates as “The Surge,” and the actual surge it depicts is one that bends not just to injustice but atrocity.