As a sometime theater critic, I try not to play for tickets and I

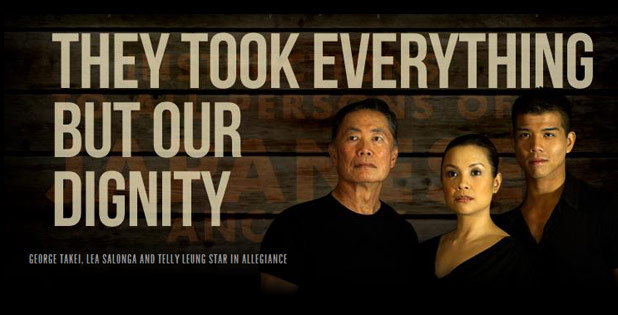

rarely sit in the front row, but for George Takei‘s musical “Allegiance”

I made an exception in 2012. That was not because I was a fan of “Star

Trek: The Original Series” or because I follow George Takei on Facebook.

I was back in Balboa Park San Diego, the place where I

learned to love theater, because an elderly relative wished to see the

show. I don’t remember ever attending theater, particularly the Old

Globe, with her, but it was something she wanted to do, and something I

could do to repay all of her past kindnesses. The show would have never

made it to the Old Globe without Takei, and ,if not for this musical, it’s

unlikely that the documentary “To Be Takei” would have been made.

Before you went into the theater, you could look at artifacts from

the past—old school yearbooks and photos. I found a photo of a relative

who has since passed away. In the photo, he was young and hopeful. I

don’t remember him that way. History had beaten him down at least in one

particular emotional compartment in one particular historical moment.

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942

came as a reaction to years of yellow perilism and the Dec. 7, 1941

bombing of Pearl Harbor. The order meant to clear the West Coast of

Japanese and Japanese Americans, first sending them to temporary

relocation camps such as the Santa Anita racetrack where people lived in

horse stalls and then to one of ten relocation camps located in various

states. The closest was Manzanar, California and the farthest east were

two in Arkansas. People lost businesses and precious family heirlooms

because they could only take what they could carry.

Being in prison is something I understand one doesn’t forget and the

internment experience is a hard, divisive matter in the Japanese

American community for two generations (the adults and the children) in

many ways. In the lobby of the theater in Balboa Park, there was an

artistic reminder of the many people who had been in the American

internment camps–Japanese nationals who were denied the right to become

naturalized citizens and Japanese Americans who were denied the rights

extended to other immigrants. Artist Wendy Maruyama had tags that

represented each inmate for each camp, gathered and hung together like

rootless trees, floating as a ghostly reminder of something that haunts

the lives of those who remember.

My relatives were divided into two mental camps: Those who can talk

about the internment and those who cannot. The number of people still

living who were confined in those Japanese American internment camps

dwindles with each passing year. Memories are being both lost and

forgotten.

In the camps themselves, a form called the Leave

Clearance Application and also known as the loyalty oath was

administered in 1943. Two questions divided the Japanese American

community into the no-no and the yes-yes. The questions were:

- “Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty wherever ordered?”

- “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America

and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by

foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or

obedience to the Japanese emperor, to any other foreign government,

power or organization?”

The no-no respondents were gathered up and sent to a different

camp and ostracized by the yes-yes community for decades after the war

ended. The musical “Allegiance” is about one family that was bitterly

divided by the questionnaire and is told through flashbacks with George

Takei playing the older present-day version of Sam Kimura and in the

1940s the grandfather. Telly Leung plays the young Sam Kimura.

My relative was touched that so many people wanted to hear this story

and that the majority of the audience weren’t ethnic Asians.

The musical had at least two unintentional consequences: 1) In

attempts to promote the musical, George Takei took to social media and

became a Facebook celebrity and 2) His prominence likely led director

Jennifer M. Kroot (with co-director and editor Bill Weber) to make the

documentary “To Be Takei.”

In “To Be Takei,” we see how being a political prisoner as a child

defined George Takei and how that and his confrontation with

stereotypes, turned into his political activism. When Takei finally came

out in 2005 and got married to his long-time companion, Brad Altman, in

2008, he also became an activist for gay rights and same-sex marriage.

To “Be Takei,” either George or Brad, means being political by showing

how normal one is and by embracing social issues with grace and a smile.

Although the documentary originally was supposed to end with the

opening of “Allegiance” on Broadway, the Allegiance team are still

working on finding a venue and crowdsourcing. It would be a pity if it

didn’t open; it would be a shame if George Takei didn’t star in it.

The musical is about the past, a memory play, but it is also about

how Americans can sometimes view Asian ethnic groups as never truly

American. It’s a lesson about the xenophobia and prejudices that surface

during wartime and that should be a lesson that is vital and timely

since we are a country at war in Iraq and Afghanistan, two Asian

countries.

We have seen an escalation of prejudice and hate crimes against

people who look like they might be from those areas and toward people of

the predominant religion there: Islam. If you think my analogy is too

far fetched, then I’ll remind people that the late Arab (Lebanese)

American Casey Kasem came together with Japanese Americans in Los

Angeles when people were suggesting that ethnic Arabs be interned. That

was in 1991, during the first Gulf War (Desert Storm) before the current

war and before Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp was established in 2002.

To “Be Takei” is to be hard working and optimistic, and I hope that it also means a successful opening and run on Broadway.