With “Fury” debuting atop the domestic box office last month

and “The Imitation Game” generating Oscar buzz in advance of its November 28

release, it would be tempting to say that Hollywood has rediscovered its

interest in World War II. The truth is it never really lost it. From the

propagandistic films made during wartime (“Sergeant York”) to modern-day remembrances

of the Greatest Generation (“Saving Private Ryan”), Americans never seem to tire

of these stories of bravery and fortitude; perhaps one reason is that the films

tell us more about the era in which they were made than the one in which they

take place.

“The Dirty Dozen” and “The Green Berets” were hawkish

rebukes to the popular anti-war sentiments of the Vietnam Era, while “Saving

Private Ryan” and “The Thin Red Line” offered more meditative, less urgent perspectives

during a time (the late 1990s) many thought to be one of protracted peace. In

the mid-2000s, Clint Eastwood made a pair of WWII films—“Flags of our Father” and

“Letters from Iwo Jima”—that examined a crucial battle from both the American

and Japanese perspectives, a stunning subversion of a genre that has

rarely made room for the enemy to be

anything other than monsters.

Eastwood’s films reflected American ambivalence over the War

on Terror, and halfway into the next decade, we remain deeply, frustratingly

divided. This may explain Hollywood’s current obsession with WWII (a third film,

Angelina Jolie’s “Unbroken,” bows on Christmas Day). Are we hungry for stories

from a simpler, more galvanized time? Perhaps, but the WWII films of today seem

made for completely separate demographics. “Fury”will resonate with people who see war as a noble and heroic

fight against evil, while “The

Imitation Game” is for those who view violence of any kind as a last

resort. The former is a hyper-violent, militaristic paean to the American

soldiers who fought the war on the battlefield. The latter is a vehicle for

progressive social values that portrays British academics as the real heroes.

The disparate values in these films are reflective of our divisive political

culture, to which apparently not even the most justifiable war in modern

American history is immune.

Nowhere are the differences between these two films more

apparent than in their depictions of violence. “Fury” is probably the most

gruesome film of the year not to exist within the horror genre. There is nothing controversial about that; war is violent, and military

veterans have praised the film for accurately reflecting its horrors, both in

its physical realities and the psychological trauma it inflicts. What separates

“Fury” from other graphic war films, however, is that it seems to celebrate killing

as an ideology, not as strategy, policy, or even self-defense.

Set in the final days of the war, when conflict is nearing

an end but, as one character puts it, “a whole lotta people gotta die,” “Fury” omits

any context beyond the battlefield. The film follows an elite tank squadron led

by Don ‘Wardaddy’ Collier (Pitt), as they receive and train an inexperienced

Army typist, Norman (Logan Lerman), who has inexplicably been assigned to their

squadron. New to the war, Norman is squeamish about killing, so Collier commands

him to shoot an unarmed German prisoner of war. When Norman refuses, Collier

literally forces his hand. Thus begins The Desensitization of Norman, a process

by which the young innocent slowly sheds his naïve, peaceful ways and learns to

relish mowing down the faceless, nameless Nazis in the tank’s path. Of course,

Norman is a handy surrogate for the audience, who will also flinch at the shedding

of blood but may be applauding the hundreds of Nazi deaths in the film’s climax.

The film’s reverence of killing runs so deep that it even

celebrates—in a way—the death of its American heroes. When the tank breaks

down, and Collier and his crew face an incoming unit of 300 or so German

soldiers, the logical choice would be to run and hide. Instead, they stay and

are rewarded with a noble hero’s death, taking out hordes of enemy soldiers in

the process. The scene recalls the second half of last year’s “Lone Survivor,”

in which 4 Navy SEALS engaged in a legendary and (mostly) fatal firefight with

the Taliban. Steven Boone, in his review here,

wrote that the film “makes political interests superfluous to

the religion of the warrior.” “Fury” walks a similarly delicate line,

condemning the horrors of war while depicting its trigger-happy protagonists as

action heroes that we are meant to emulate.

The comparison to “Lone Survivor” works especially well when

we consider “Fury” a reflection of our attitudes towards our current war

against global jihadism, an enemy that some consider equal to the Nazis in

their practices and ideology. Like many who support increased American presence

in the Middle East, “Fury” sees global conflict as a zero sum game, in which

total destruction of our monstrous enemies is the only goal. Such a perspective

may not accurately reflect global realities—the war on jihadism cannot be won on

guts and glory alone—but it also ignores the fact that support for America’s

involvement in WWII was hardly unanimous, at least until the Pearl Harbor

bombing. In fact, until that point, the U.S. resisted involvement in the war at

every turn, but in our films and other pop culture artifacts, that ambivalence

has been mostly stripped from the record. “Fury” marks the latest film to

depict WWII as a simple, inarguable case of good versus evil, which, in all the

ways it deviates from reality, makes for a gripping movie with a satisfying

moral canvas.

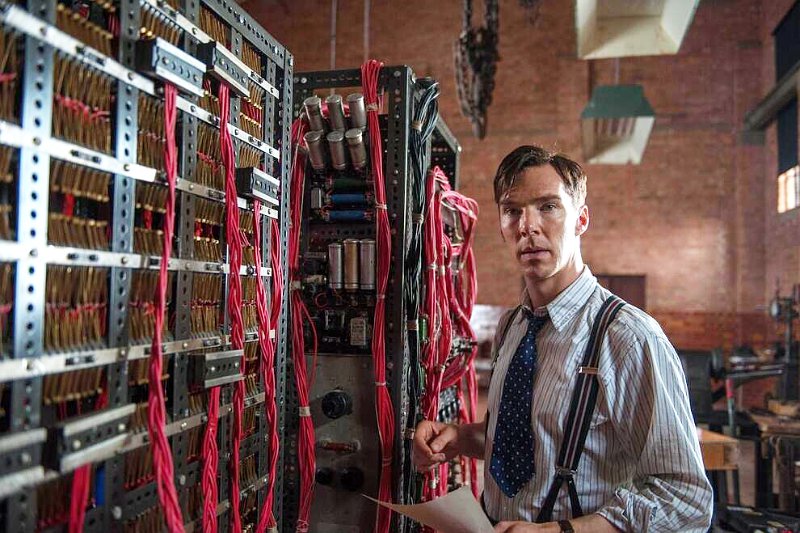

“The Imitation Game” makes its own moral calculations, but

from the inverse perspective. Its characters never even sniff the battlefield,

with almost the entire story taking place inside the abandoned radio factory

where genius mathematician Alan Turing (Benedict Cumberbatch) and his team

labor to crack the Nazi Enigma code. The heroes of the film are quiet,

unassuming academics, who have more in common with Norman at the start of “Fury”

than any of that film’s hardened war veterans.

The film’s attitude towards violence is best displayed in the

crucial moment after Turing cracks the code. After discovering through decoded

messages that German U-boats are planning on attack on a British passenger ship

that will kill hundreds of men, women, and children, he decides to let the

civilians die, instead of saving them and inadvertently alerting German

intelligence that their code has been cracked. Every day after that, Turing and

his team make a “blood-soaked calculus” to determine how many lives they can

save, while still preserving their secret of having cracked the code, their

greatest tool in winning the war. In this way, “The Imitation Game” puts the

strategic and moral choices of war in the foreground, whereas “Fury” ignores

them altogether.

If the characters in “The Imitation Game” seek to avoid

bloodshed—or are at least “agnostic” about it, as Turing puts it—it could be

because they themselves have been the victims of systemic cultural violence. Turing

and his most trusted partner, Joan Clarke (Keira Knightley), are a closeted

homosexual and a woman, respectively, and the film places their accomplishments

in the context of the LGBT and gender equality movements. Turing ends up arrested

for indecency and sentenced to hormone therapy, also known as “chemical

castration.” Meanwhile, Clarke is mistaken for a secretary when she first

reports to work for Turing (the security guard can’t believe a woman would be

smart enough), and she views her work as an escape from the domestic life women

of her generation were expected to fulfill. As Turing and Clarke form a strong,

platonic relationship, the film touchingly shows how cultural violence towards marginalized

people can force them into strange, difficult choices, but also how their

shared struggle can forge strong bonds of friendship.

Turning the classic World War II movie into a vehicle for

socially progressive values is a pretty subversive act, and the film’s boldness

is likely to get it some serious awards attention. Alternatively, the

left-leaning Academy will surely reject “Fury,” despite the great love it has

received at the box office and from the military community. Maybe that’s okay. The

near-simultaneous release of these two films—buttressing the mid-term elections,

no less, when political ideologies are running highest—may show how well

Hollywood is adjusting to our political divisions. For most of the last 70

years, you could make a WWII film that appealed to the masses. Nowadays, you

have to make two.