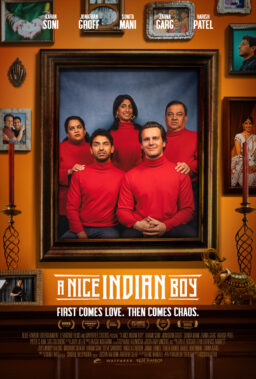

Author and philosopher G.K. Chesterton wrote in his story collection, Tremendous Trifles, “The world will never starve for want of wonders, but only for want of wonder.” Director Isaiah Saxton’s directorial debut, the fantasy adventure film “The Legend of Ochi,” feels like a warning against the beauties we might overlook if we let fear, instead of wonder, dictate how we navigate the world.

“The Legend of Ochi” takes place on the remote island of Carpathia, where we meet Yuri (Helene Zengel), who has been raised to fear the Ochi, simian-esque creatures with distinctively elongated ears and orange fur. One day, she discovers a baby Ochi caught in a trap, and going against her community’s wishes, she embarks on a journey to return it to its family.

Willem Dafoe plays Maxim, Yuri’s father, who leads a group of young boys on hunts against the Ochi. He’s the only character who wears a full suit of Viking-inspired armor (the rest of the boys wear civilian garb), which further highlights how Maxim operates at his own deranged tempo.

From Maxim’s tendency to go on diatribes to his crazed, hate-fueled expressions, he’s a character who’s cut from the similar berserk cloth of Dafoe’s other characters, like Paul from “The Boondock Saints,” Geiger from “Speed 2: Cruise Control,” and Thomas in “The Lighthouse” to name a few. Yet Dafoe shades his unique flavor of demented with an open-hearted earnestness.

“You may think me nasty and grim, but remember my dears … I know your pain,” he tells the boys under his tutelage when they begin to feel the burden of Maxim’s crusade. No matter how many times you may think you’ve seen Dafoe play crazy, he manages to access a deeper layer of humanity that grounds even his most histrionic characters. He does the same with Saxton’s film.

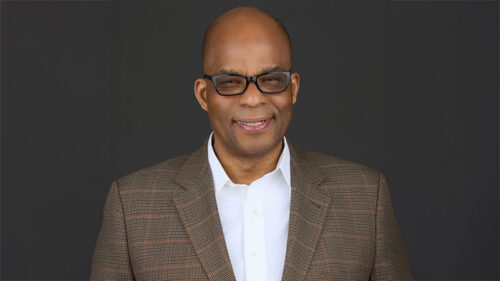

For Dafoe, imbuing the unknown into the familiar has become his modus operandi at this stage in his career. “I’m interested in new ways of saying much more than just empathy,” he shares. Ahead of the film’s wide release, Dafoe—with a welcome interruption from his dog—spoke briefly with RogerEbert.com about wardrobe as a way to unlock the interiority of a character, the importance of wonder in his creative process, and how his work in the film connects with his recent appointment as Artistic Director for Venice Biennale’s 53rd International Theater Festival.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

You’ve described the difference between working with practical effects versus green screen as the difference between writing a love letter by hand or on a computer. The imperfections are part of the charm. I’m curious about what imperfections you may have felt in your performance that you had to learn to embrace while working on this film.

There’s a lot that you can’t control, particularly when you’re shooting outside in nature, although this was a fairly brisk shoot. I don’t know, though. I don’t particularly welcome imperfections, but I accept them when they come organically. Maxim is a bit of a fuckup so that was an interesting entry point into embodying him. Sometimes you can’t tell the difference between Willem’s fuckup and Maxim’s fuckup (laughs).

The outfit changes Maxim goes through is also a fascinating way to trace his fuckups. He’s the only one with a helmet; he doesn’t use guns like the boys do, but uses axes and spears. How do you think about wardrobe as a way to access the character you’re playing?

Your ability to pretend is strengthened based on how much your wardrobe makes you feel different. It helps you see yourself differently. Maxim is the only one who wears a full suit of armor throughout the film, and it’s quite wacky. It takes you out of any kind of association because it’s wrong for the situation he and the boys find themselves in. That sense of disconnect was made palpable through what I had to wear. Within the story, it makes sense because he’s putting on this battle gear that connects him to the past, and it makes him stand out as a leader to these little kids who stand next to him, who aren’t wearing it. Looking at all of us, we’re a charming ragtag group, and that sense is amplified due to what I’m wearing. When you have a good costume, the costume tells you what to do.

I’m thinking now of the prosthetic teeth you had to wear for Bobby Peru in “Wild at Heart.”

(Laughs) Well, the teeth didn’t just help my performance … they were Bobby Peru!

Maxim is a character who uses fear-mongering tactics as a way to radicalize the youth under his tutelage to cause violence. I’m curious to know how playing a character like that resonated with you in light of our current moment.

It’s all in the writing and story. I had a good setup thanks to Isaiah. Maxim is an interesting character because he is selling this fear, but throughout the film, he comes to see the world in a different light and also comes to see his daughter in a new way. There’s enlightenment at the end of his radicalization.

Throughout your career, you’ve spoken a lot about the importance of stewarding the Earth and the environment. Projects like “The Legend of Ochi” explore humanity’s insignificance, the value of wonder, and our feeble attempts to articulate the unarticulable. What role does wonder have in your creative work?

Wonder is everything. It’s funny; I use that word maybe too much because it expresses a state that you want to achieve. Wonder is a way to challenge your conditioned responses to things. Much of our current way of “seeing” and existing in this world is based on function and what things mean. Sometimes it’s better to get beyond that, to find the origins of something, and to find the essence of what something is. That clarifies our lives in the context and place of the greater world and our place in this time while we’re here on this Earth.

So, when you say ‘wonder,’ I am just thinking about challenging and inviting people into a different way of seeing. Once you have that other way of seeing, it opens you up to being free. When you think of wonder, I think of a kind of awe or appreciation for how everything is connected and how there is a kind of otherworldly logic or order to things. You could say it’s almost a spiritual thing.

When you’re able to connect with that, it makes you live your life more gratefully and constructively. It enables you to be kinder to yourself and to other people. In the context of “The Legend of Ochi,” I think that’s exactly what Isaiah is trying to float. It’s easy to say but hard to achieve. I say all this as I pet my dog here (laughs).

We rarely leave room for mystery in our day-to-day lives.

It’s so important to leave that room, though. We—I should speak just for myself—but we’re always confronting what stuff means. We’re logic and efficiency-obsessed, and we forget to breathe and be reborn every day.

You now serve as artistic director for La Biennale di Venezia, and when crafting the program, you considered works that express the power of the theater—the body, poetry, and ritual. That all comes into play in “The Legend of Ochi.”

That’s good! That’s very important to me.

I’m curious to know how you see your work, as Maxim, as a continuation of that trio of themes.

Performance is about accessing the intelligence of the body that’s beyond what we can initially grasp. I’m struck by how many functions of the body are beyond our volition. Not everyone can appreciate that. The reality I always come back to is the fact that right now, through Zoom, I’m looking at you. But what I’m seeing right now, wherever you are, it’s just an image of you. It’s mind-boggling! You’re in another place, but for this image of you to be accomplished in a sense, millions of things have to happen, from the technology that enables this to the eyes that behold you.

Where does that come from? I’m not consciously doing anything. If you have respect for the body and its functions, then you appreciate that something is working through you. As an extension, you encourage that and you try to direct it with a particular kind of discernment. Once you commit and serve an action, there’s a kind of presence that’s alive and that’s one of the keys to performing, I think. This is particularly felt in the theater because you’re seeing things as they’re happening. The temporality of the theater is the beauty of the theater.

As for the ritual aspect, in movies like “The Legend of Ochi,” where you come in and do a scene quickly or visit a location for the first time and shoot, there are motions you go through, even in an improvised performance. With a project like this, I was repeating similar actions as a sort of ritual.

As for poetry, especially with something like “The Legend of Ochi,” it’s about inviting yourself into that wonder you mentioned and moving away from a particular kind of practicality. I may be butchering the expression, but when I played T.S. Eliot in “Tom & Viv,” one of the many beautiful things he said was, “Poetry is not a letting of the emotion … it’s an escape from emotion.” So it was to bring you to a kind of logic and clarity, and I think somewhere that’s what I’m interested in. I’m interested in exploring new ways of expressing more than just empathy. Empathy is great, but you get on the bus and forget where you came from. It’s the difference between how people travel sometimes, whether they’re just rushing to a destination or living moment by moment, going towards someplace where they aren’t quite sure what they need from that place.

By the end of the film, Maxim has been gifted not just empathy but a new way of seeing the Ochi’s.

It’s true.