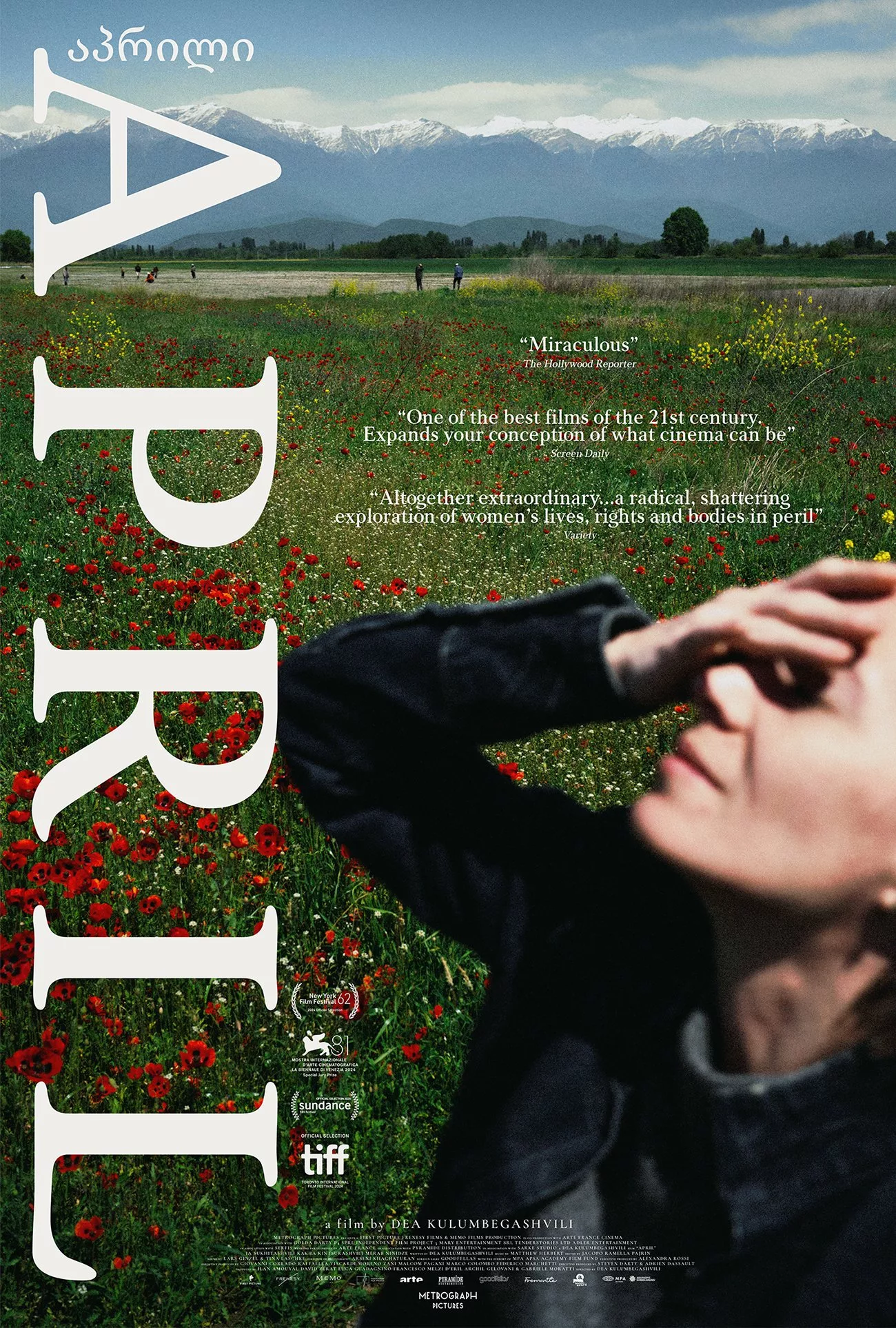

“April” is as exquisite as it is excruciating: a film that will linger with you long afterward, but you’ll probably never want to watch it again.

This is a testament to the power of Dea Kulumbegashvili’s artistry. In only her second feature, the Georgian writer-director has crafted a film filled with images that will sear into your mind, even as they challenge your patience. She favors long, static takes that may frustrate you, even as you admire their beauty or the boldness of their framing. While it may be difficult to discern what Kulumbegashvili’s aim is in the moment, the cumulative effect of her storytelling approach packs an undeniable wallop.

“April” haunts from its opening shot of a mysterious form, wandering slowly about a black void covered with water, an image that calls to mind Jonathan Glazer’s gorgeous sci-fi thriller “Under the Skin.” The figure is naked but not quite human, upright but saggy and gnarled. There’s a striking disconnect between what we’re seeing and what we’re hearing: the joyful sound of kids laughing and playing. Kulumbegashvili has thrown down a challenge from the start.

But just when you think she’s lulled you in, she shocks you with a bright and graphic overhead shot of a woman giving birth. The baby ends up being stillborn, and the OB/GYN, Nina (Ia Sukhitashvili), comes under scrutiny for her handling of the mother’s pregnancy. We’ll soon learn that Nina travels to nearby villages in her off hours to provide birth control and abortions to women who need these services and can’t afford them. More crucially, they dare not ask for such medical help within this rigid, patriarchal society.

Nina is clearly brave, but “April” takes its time in showing us this doctor in full, perhaps because she can’t even view herself that way. We see her from the back, from the side, from afar—or we see the world from her perspective as her eyes dart left and right on a rural road as she’s driving, her breath quickening. Cinematographer Arseni Khachaturan, who also shot Luca Guadagnino’s “Bones and All,” helps create this mesmerizing imagery, often at night or in low light. And the fact that Kulumbegashvili shot “April” in boxy Academy ratio emphasizes Nina’s isolation and her struggle to break free from societal restraints.

“There’s no space for anyone in my life,” she tells her fellow doctor and ex-lover, David (Kakha Kintsurashvili), in a rare moment of communicating actual human emotion. With her sleek frame, blunt bob and big eyes, Sukhitashvili offers a quietly imposing screen presence. But while Nina may seem mysterious or aloof, the care she feels for her patients and the weight of her calling are obvious.

It’s the unspoken that speaks volumes in “April,” often in long, single takes that last well past the point of discomfort. This is especially true during a scene in which Nina performs a kitchen table abortion for a deaf-mute teenager. The camera holds steady on the young woman’s torso and the right hand her mother is holding to comfort her. The fact that this procedure is necessary in such a setting feels like both a wail of anguish and a battle cry against society.

But there’s also beauty to be found here, whether it’s a field of bright red poppies, the thick gray of a gathering storm or a pinky-purple pre-dawn sky after a long and difficult night. That’s when Nina wakes up early to dislodge her car from where it got stuck in the mud during heavy rainfall—how’s that for a metaphor?

Shocking things happen in understated ways in “April.” It’s a hard watch. And that’s the point.