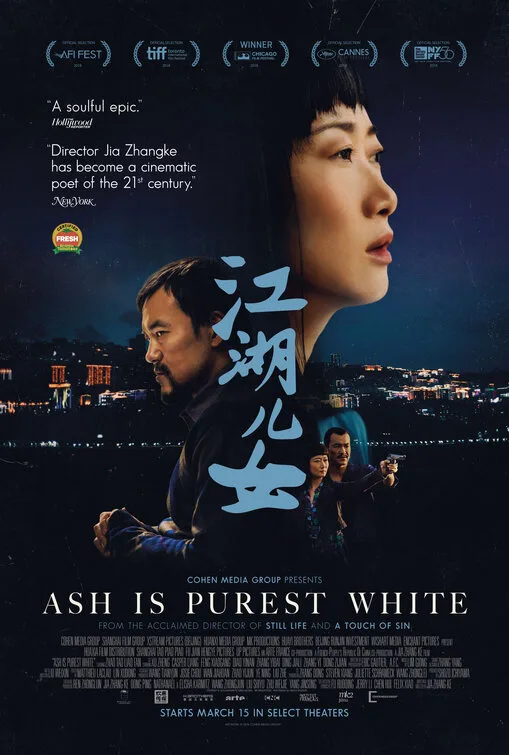

The English subtitles for this superb film from China leave one word untranslated: “jianghu.” It refers to outlaw sects or societies and is literally untranslatable, but for the main character of this movie it means not just “gangster” or something like it; it connotes a particular code of ethics.

The character for whom this meaning is most sacrosanct happens to be a woman. In the movie’s opening scenes, set around the turn of the 20th century, Qiao, played in a spectacular performance by Tao Zhao, swaggers into an underground mahjong parlor like it ain’t no thing, taking her seat next to gang big shot Bin and taking a few drags from his cigarette. When Bin mediates a conflict between his subjects, talking one of them into putting aside a pistol he’s just rashly brandished, Qiao picks up the gun and examines it with no small fascination.

Bin and Qiao are soon revealed to be rather more serious people than these first impressions indicate. Qiao has an ailing dad whose loss of a profession—he worked in a mine that’s soon closing—isn’t helping his disposition. Bin likes a peaceable rule, even as he offers to help out an elder operator who’s delving into real estate. “Some assholes are saying my villas are haunted,” the older guy complains. Before Bin can look into it, that guy is knifed in a parking lot.

Bin is caught up in an unspecified turf war that culminates when he’s attacked by about a dozen youths who brutally beat him. It’s Qiao who takes definitive action to save him—and winds up doing five years in prison for her trouble.

Like his prior film, 2015’s “Mountains May Depart,” this new picture from master Jia Zhangke is a three-part drama spanning decades. To this critic “Ash is Purest White” is a much more successful attempt at depicting a changing China through the lives of not-quite-tragic characters and their sufferings.

Once Qiao is sprung from prison, it’s 2006, and the monumental Three Gorges project, which was to transform permanently the Yangtze River, is underway. She takes a boat in search of Bin, is ripped off by a pretend-pious woman sharing her cabin, and has to chase her old boyfriend down to get him to fess up about his new life, which isn’t much to speak of. After a time is becomes clear that Qiao’s heartache isn’t merely over the loss of a boyfriend, but of the loss of a way of life. This compels her to embrace the jianghu code, or at least her interpretation of it, with even more ferocity. By the time we hit 2018, she’s completely transformed herself, much like the railway she took to get away from Bin after their unsatisfactory reunion.

Because Jia sets the final section of the film in the present day, as opposed to a rather sketchy not-too-distant-future he traveled to in “Mountains,” “Ash” resolves with a genuine immediacy. And his living-outside-the-law characters here are simply more compelling than the betraying strivers of the prior film. The movie represents both the director and his lead actress at the peak of their powers. Tao Zhao presents Qiao first as a tough kitten of sorts; during her prison stint, she looks drawn and wan, and stays seemingly timid upon release. Gradually, though, the actress shows that Qiao has indeed grown into a lioness. Albeit one that’s not just fearsome, but reflective and wise.

The movie is always a pleasure to behold, but be warned: The sound mix is so acute that every time one of the characters’ iPhones went off in the present-day scenes I was almost annoyed, thinking that someone in the screening room had left their device on. So wait a second in your local arthouse before yelling “turn it off!”