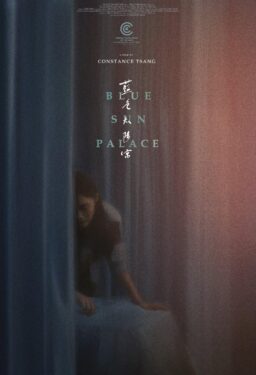

When movies hold off on displaying their title until the story gets going in earnest—think “Babylon” or “Fresh,” as well as the Oscar-winning “Drive My Car”—they usually are after establishing a feeling, or the reality of a group of characters in the story that we’re about to experience. But when the debuting writer-director Constance Tsang does it in her lyrical and specific mood piece “Blue Sun Palace,” she stylishly and compassionately does so to introduce a tragedy, leading us into the aftermath of it.

Her quietly affecting film places us in the midst of a Chinese community in Flushing, Queens, an enclave of New York City typical films about the Big Apple don’t necessarily navigate frequently. In the beginning, her tale (filmed almost entirely in Mandarin) is chiefly about three immigrants. Two of them are the Taiwanese Amy (Ke-Xi Wu), and her mainlander friend and colleague Didi (Haipeng Xu), a duo working at a massage parlor, serving mostly an entitled male customer base. Even when the sign on the door clearly communicates that they’re not the kind of spa that offer sexual services, some of their slimy clients aren’t above demanding a “happy end” all the same in exchange of a larger tip (which they don’t always deliver upon). In short, there isn’t anything all that rewarding about the work, but the two, surrounded by a group of other women, find a warm and cozy camaraderie in each other’s company. It also helps that Didi and Amy have a plan worked out for themselves—save enough to open a restaurant in Maryland where Didi has family, and leave the massage parlor behind.

The third character we follow is Didi’s man-of-few-words boyfriend Cheung (played by the great Lee Kang-sheng, a staple of the films of Tsai Ming-liang), a married Taiwanese construction worker sending money to his sick mother, as well as wife and daughter back home. At the start of the film, the Cheung and Didi share a spicy chicken dish at a no-frills restaurant, giving us a taste of both their culture’s culinary flavors (that “Blue Sun Palace” frequently honors), and the kind of easy intimacy they’ve come to form with one another over time. The film’s cinematographer Norm Li stays close to their faces and bodies for a while, making sure that every touch and facial gesture counts between these characters when they dine and passionately fall to bed. This style repeats until the title card emerges, bringing along with it an unspeakable catastrophe upon which Didi quietly exits the film.

Well, she does so in flesh only, as her heartbreaking absence informs much of what’s to come. As such, Tsang deepens the themes of her movie in unhurried doses, bringing to the surface the loneliness, isolation, and displacement of the remaining characters. Especially affected by Didi’s absence after some time (Tsang smartly doesn’t spell out how much time), Amy struggles with the ebb and flow of depression, with her once conceivable “American Dream” looking like a distant memory with each passing day. Grief—over both Didi, and the loss of her grand dreams—eventually bring Amy and Cheung closer, with the latter struggling with his own share of questions about this strange country they’re both stuck in. Tsang doesn’t make any grand statements about what the future might hold for them, or for the many immigrants who are trapped within a similar cycle. Instead, she focuses on the mundanity of their everyday life. On the one hand, there are more meals to share, there is physical intimacy, and there is the relief of waking up to a new day. But on the other, there is a new massage parlor creeper who begs for a happy end, but doesn’t pay what he promised.

As these themes gain further complexity, Li’s camera also follows suit with a number of interesting composition choices that emphasize the characters’ respective remoteness with a lens that sees them from further distances on occasion. Elsewhere, Sami Jano’s sparse yet poetic score echoes the feeling of melancholy on the screen, without being preachy or prescriptive.

Tsang has made a small, affecting, and studiously minimalist film here, with lived-in and tactile visual and design elements signaling a major auteur in the making. In a lot of ways, her film brings to mind “Take Out,” a stunning early Sean Baker movie about a Chinese immigrant working as a deliveryman. Inspired by her and her family’s own past as immigrants, Tsang’s poignant “Blue Sun Palace” is anchored in a similar kind of empathy, one that lingers and grows long after the film’s aching end credits appear.