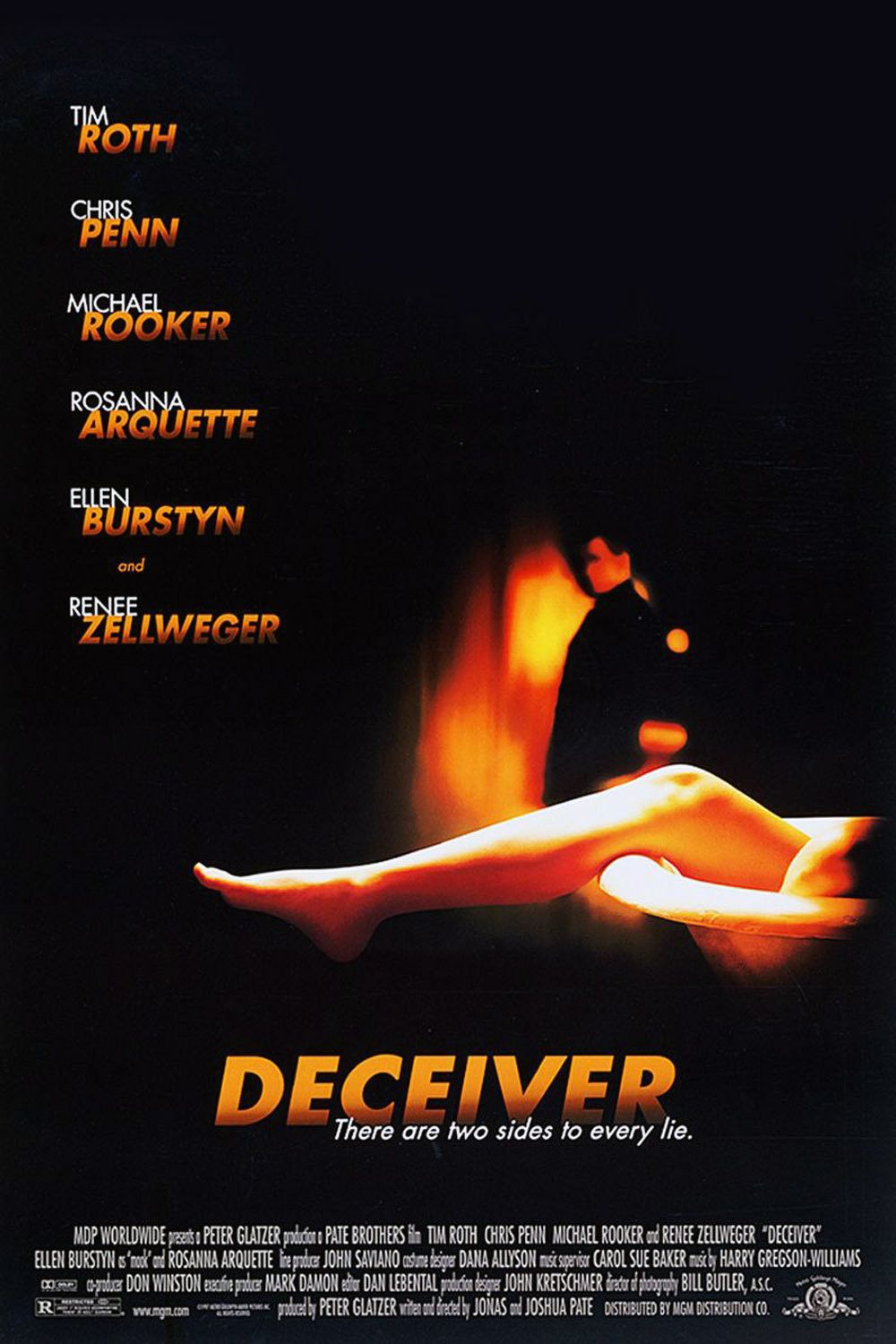

“Deceiver” is a Chinese box of a movie, in which we learn less and less about more and more. It’s centered in a police interrogation room, where a rich kid undergoes a lie detector test in connection with the murder of a prostitute. Did he do it? At first it seems he did. Then he turns the tables on the two cops running the polygraph exam, and by the end of the film everyone is a suspect.

Tim Roth stars as Wayland, a Princeton grad and the son of a textile magnate, but currently unemployed. There’s no doubt he knew the prostitute, named Elisabeth (Renee Zellweger, from ”Jerry Maguire”). He even took her to a black tie party at his parents’ home and got disowned in the process. But did he cut her into pieces and distribute her throughout Charleston, S.C.? The cops are Braxton (Chris Penn) and Kennesaw (Michael Rooker). Their methods are a little crude; they seem intent on helping Wayland fail the test, with intimidation and hints he isn’t doing too well. Wayland responds with all the cockiness and self-assurance of a man who knows he’s not so much a suspect as a character in a movie, taunting the cops with inside information about their private lives.

”Deceiver” is similar to ”The Usual Suspects” in the way it coils around its central facts, looking at them first one way and then another. It also has a less obvious parallel with Quentin Tarantino’s practice of working arcane knowledge into the dialogue of his characters. Carefully polished little set pieces are spotted through the film; the action stops for well-informed discussions about Vincent van Gogh, the dangers of absinthe, the symptoms of epilepsy and the relative intelligence of the two cops.

There wasn’t much I could believe. The movie is basically about behavior–about acting, rather than about characters. The three leads and some supporting characters get big scenes and angry speeches, and the plot manufactures big moments of crisis and then slips away from them. It feels more like a play than a movie.

One of the ways it undermines its characters is by upstaging them with the plot. We get several theories about the death of the prostitute, and lots of flashbacks in which Wayland’s tortured childhood offers explanations for actions he may or may not have taken. Facts are established, only to be shot down. Having seen the film twice, I am prepared to accept that its paradoxes are all answered and its puzzles solved, although unless you look closely and remember the face of an ambulance driver, you may miss the explanation for one of the big surprises.

The thing is, even after you figure it all out, a movie like this offers few rewards. It’s well-acted, and you can admire that on a technical level, but the plot is such a puzzle it shuts us out: How can we care about events that the movie itself constantly undercuts and revises? By the time the final twist comes along, it’s as if we’ve seen a clever show in which the only purpose, alas, was to demonstrate the cleverness.