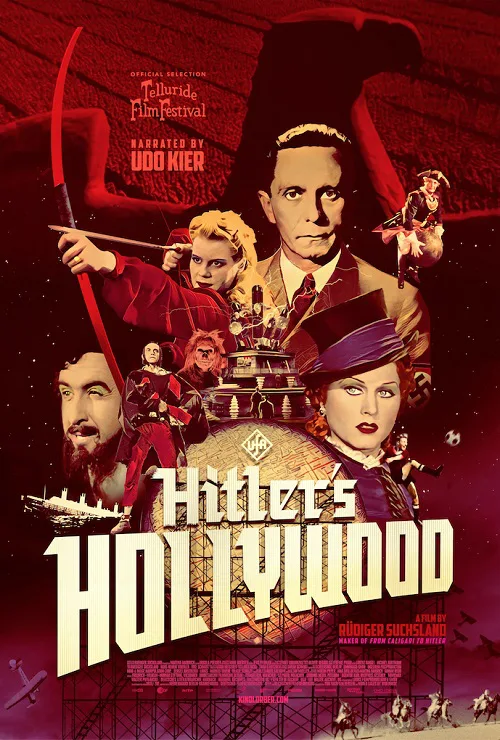

“Hitler’s Hollywood,” which bears the subtitle “German Cinema in the Age of Propaganda: 1933-45,” is the second documentary director Rudiger Suchsland has made about German movies prior to the collapse of the Third Reich. The first, “From Caligari to Hitler,” was based on the groundbreaking 1947 book of the same title by Siegfried Kracauer, which surveyed the cinema of the Weimar Republic and thus includes many of the masterpieces by Lang, Murnau, Pabst, et al. that Western cinephiles have studied and enjoyed for generations.

The new film is different from its predecessor in that hardly any of the movies it covers will be familiar to viewers outside Germany, and only one, a very controversial display of Nazi triumphalism by Leni Riefenstahl, can be remotely considered a world-cinema classic. With that distinction made, the first thing to say about “Hitler’s Hollywood” is: it’s quite a show—a cavalcade of images, icons and ideas that, while less innovative, are every bit as eye-popping in their own way as “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari,” “Nosferatu” and “Metropolis” are in theirs.

Which is not to say that the Third Reich’s cinema was the breeding ground for auteurs that the Weimar years had been. On the contrary, Suchsland makes the claim early on that Nazi Germany had a single auteur: Joseph Goebbels. Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda (whose years in the post coincide exactly with those covered by this film) was the consummate master of totalitarian thought control. He was in charge of radio, propaganda, and all branches of the arts; but as he considered film the most important of these, he exercised complete control over the production of German movies, right down to the particulars of scripts and casting.

Germany produced over 1000 movies in the Nazi era, and relatively few of these were pure propaganda. Riefenstahl’s “Triumph of the Will,” ordered by Hitler himself to celebrate the consolidation of his cult at the 1934 Nuremberg rally, was, as Suchsland notes, an incredible fusion of eroticized imagery and editing with quasi-religious spectacle using geometric masses of people much as the Nazi entertainment films would. The notorious “Jud Suss” (1940), ordered by Goebbels himself, was virtually an order for Germans to slaughter Jews; seen today, one of its crucial scenes uncomfortably recalls the racism of D.W. Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation.”

But it’s the entertainment films here that exercise the greatest fascination. Some are obviously meant as pure escapism, while others embed—subtly or not—propagandist ideas or messages in their fictional stories; and there’s quite a lot of gray area between the two categories. Death and the nobility of dying for the fatherland were recurrent themes, even before the war began. And though families are idealized, the idea of subjugating the individual to the mass was constantly stressed. In one early Nazi propagandistic drama, a boy who distances himself from his Communist father to join the Nazis is valorized, and naturally ends up dying nobly with his eyes fixed on a swastika banner fluttering above him.

Hitler, it is said, was holed up at home watching Mickey Mouse, Frank Capra movies and musicals, which led Goebbels to try to Hollywoodize some of the Nazi cinema. But Germany already had an advanced industry for producing entertainment movies, and “Hitler’s Hollywood” provides countless examples of its technical sophistication. Horror and fantasy films were out (they might take viewers too close to underlying psychic troubles, it is suggested) but musicals, melodramas, romances, military and adventure movies were among the genres that flourished. There are only a few glints of Teutonic comedy here, though, and Suchsland wryly notes the films’ almost “total lack of irony.”

Though Marlene Dietrich had already decamped for Hollywood, and Ingrid Bergman, aged 23, passed through and made one feature which she later regretted, Germany had a fully developed star system that evolved throughout the period. As in Hollywood, there was a vogue for foreign stars, especially females from countries including Sweden and Hungary. The names of these accomplished performers are too numerous to list here, but their work is well worth discovering, and I think I share with Suchsland a fascination with two in particular: Gustaf Grundgens, an actor whose work remains stunning in its daring and skill; and Ilse Werner, whose looks and very modern elan might have made her a star in Hollywood or the French New Wave.

Of the directors whose work is most frequently seen here, very few saw their careers ended by the collapse of the Third Reich; most went on to work in post-war Germany (even “Jud Suss” director Veit Harlan, who claimed he was just following Goebbels’ orders and actually toned down the film’s antisemitism). And it’s not like Germany was completely bereft of auteurs. As we see, G.W. Pabst, having failed to escape in time, made “Paracelsus,” which looks like a medieval allegory of irrationality rampant. And then there’s the case of Detlef Sierck. Someone should make a doc exploring the connections between his work in Germany and the movies he was acclaimed for after he moved to Hollywood and became Douglas Sirk.

Suchsland judiciously quotes Kracauer as well as Hannah Arendt and Susan Sontag, and in the film’s narration—voiced by Udo Kier—he touches on themes having to do with mass psychology and the German soul, wondering what elements continue today even though many people might prefer to think they have been left behind. Yet most of these ideas are rather superficially invoked (other issues, like Goebbels’ hostility toward the church, are overlooked entirely); treating them in depth obviously would require a much longer film or series. (Suchsland reportedly plans a third film covering the post-WWII cinema.)

Finally, one can’t watch this film and not think of events in the world today. How did the German nation get so caught up in the Nazi mythology that it plunged willingly toward its own destruction? Obviously being seduced away from a clear comprehension of reality into self-regarding mass fantasy was a big part of it. As “Fox & Friends”—I’m not talking about a Fassbinder movie here, folks—and similar phenomena today suggest, the credulousness and suggestibility that lead to such disasters is not just a German condition.