Now here is true evil: Cold, unblinking, reptilian. The character Chad in “In the Company of Men” makes the terrorists of the summer thrillers look like boys throwing mud-pies. And for every Chad there is a Howard, a weaker man, ready to go along, lacking the courage to disagree and half intoxicated by the stronger will of the other man. People like this are not so uncommon. Look around you.

The movie takes place in the familiar habitats of the modern corporate male: Hotel corridors, airport “courtesy lounges,” corporate cubicles. The men’s room is an invaluable refuge for private conversations. We never find out what the corporation makes, but what does it matter? Modern business administration techniques have made the corporate environment so interchangeable that an executive from Pepsi, say, can transfer seamlessly to Apple and apply the same “management philosophy” without missing a beat.

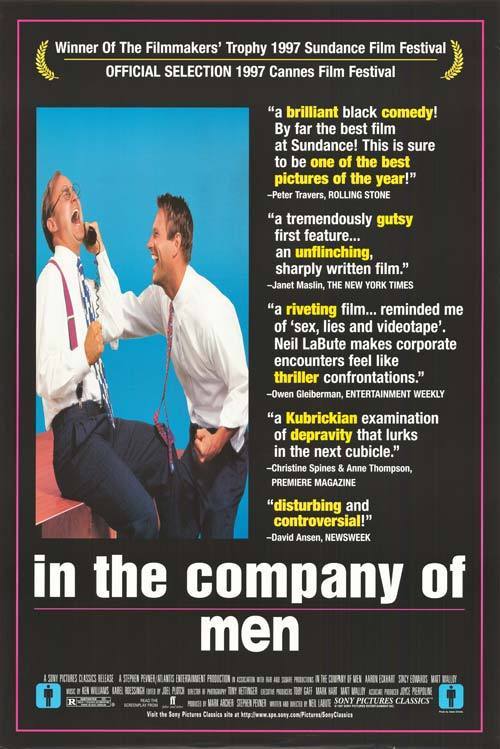

Chad (Aaron Eckhart) and Howard (Matt Malloy) have been assigned for six weeks to a regional office of their company. Waiting for their flight, they talk. Chad is unhappy and angry because he’s been dumped by his girlfriend (“The whole fade-out thing”). He proposes a plan: “Say we were to find some girl vulnerable as hell … ” In their new location, they’ll select a young woman who doesn’t look like she has much of a social life. They’ll both shower her with attention–flowers, dinner dates–until she’s dizzy, and then, “out comes the rug, both of us dropping her!” Chad explains this plan with the blinkered, formal language of a man whose recreational reading consists of best-selling primers on excellence and wealth. “Life is for the taking–is it not?” he asks. And, “Is that not ideal? To restore a little dignity to our lives?” He hammers his plan home in the airport men’s room, while Howard, invisible behind a cubicle door, says he guesses he agrees.

The “girl” they choose for their target turns out to be deaf–a bonus. Her name is Christine (Stacy Edwards). She is pleasant, pretty, articulate; it is easy to understand everything she says, but Chad is cruel as he describes her to Howard: “She’s got one of those voices like Flipper. You should hear her going at it, working to put the simplest sounds together.” Howard makes a specialty of verbal brutality. Christine is not overwhelmed to be dating two men at once, but she finds it pleasant, and eventually she begins to really like Chad.

“In the Company of Men,” directed by Neil LaBute, is a continuing series of revelations, because it isn’t simply about this sick joke. Indeed, if the movie were only about what Chad and Howard do to Christine and how she reacts, it would be too easy, a one-note attack on these men as sadistic predators. The movie deals with much more and it cuts deeper, and by the end we see it’s about a whole system of values in which men as well as women are victims, and monstrous selfishness is held up as the greatest good.

Environments like the one in this film are poisonous, and many people have to try to survive in them. Men like Chad and Howard are dying inside. Personal advancement is the only meaningful goal. Women and minorities are seen by white males as unfairly advantaged. White males are seen as unfairly advantaged by everyone else.

There is an incredibly painful scene in “In the Company of Men” where Howard tells a young black trainee, “they asked me to recommend someone for the management training program,” and then requires the man to humiliate himself in order to show that he qualifies. At first you see the scene as racist. Then you realize Howard and the trainee are both victims of the corporate culture they occupy, in which the power struggle is the only reality. Something forces both of them to stay in the room during that ugly scene–job insecurity.

On a more human level, the story becomes poignant. Both Howard and Chad date Christine. There is an unexpected emotional development. I will not reveal too much. We arrive at the point where we thought the story was leading us, and it keeps on going. There is another chapter. We find a level beneath the other levels. The game was more Machiavellian than we imagined. We thought we were witnessing evil, but now we look on its true face.

What is remarkable is how realistic the story is. We see a character who is depraved, selfish and evil, and he is not a bizarre eccentric, but a product of the system. It is not uncommon to know personally of behavior not unlike Chad’s. Most of us, of course, are a little more like Howard, but that is small consolation. “Can’t you see?” Howard says. “I’m the good guy!” In other words, I am not as bad as the bad guy, although I am certainly weaker.

Christine survives, because she knows who she is. She is deaf, but less disabled than Howard and Chad, because she can hear on frequencies that their minds and imaginations do not experience. “In the Company of Men” is the kind of bold, uncompromising film that insists on being thought about afterward–talked about, argued about, hated if necessary, but not ignored. “How do you feel right now, deep down inside?” one of the characters asks. The movie asks us the same question.