In many interpretations of her story, Mary Queen of Scots was a woman who wanted power and love and ended up with neither. And although this tragedy played out on one of the largest stages of the 16th century, her story is often relegated to the footnotes under that of Queen Elizabeth I, her cousin and professional nemesis, who’s been portrayed in movies by a royal line of actresses including Bette Davis, Judi Dench, Helen Mirren, Vanessa Redgrave and Cate Blanchett. Yet while cinema has not been as kind to Queen Elizabeth I’s younger cousin, first-time director Josie Rourke’s “Mary Queen of Scots” reimagines the northern queen’s demise as one caused not by her ambitions but by the treacherous men who lied to her and about her.

This time, Mary is brought to the big screen as a headstrong leader played by Saoirse Ronan. The actress follows in the footsteps of Redgrave and Katharine Hepburn, both of whom performed the role of the doomed monarch with fatalistic grace. In movies, as in life, these versions of Mary show her as a devout Catholic whose rule was challenged by the men around her—like those on her council, her second and third husbands and even the men outside her castle. However, much of the movie is dedicated to Mary’s attempts at becoming the successor to the English throne by Queen Elizabeth I (Margot Robbie).

Yet for all her tenacity, Mary never gains the full loyalty of her people for various reasons, including her religion, her French first husband, her subsequent marriages and other rumors of infidelity. A Trump-like Protestant preacher John Knox (David Tennant) regularly speaks out against her, and his misinformation campaign eventually convinces her subjects to disown her. Coupled with her disastrous marriage and several more betrayals of trust, the queen is forced to abdicate the throne, leading her to an untimely fate.

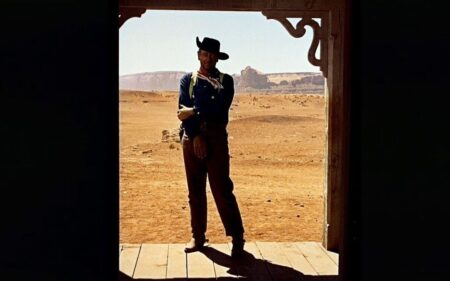

Rourke, who comes to the film industry from the theater, has an eye for pageantry and staging that make even dull conversations about power struggles feel lively. John Mathieson’s oil painting-like cinematography plays well with the regal costumes of Alexandra Byrne, who’s known mostly for her work on several Marvel movies. Byrne’s outfits are color-coded to enhance the differences between the stiff-collared English court and the dark ruggedness of their Scottish counterparts. Through Mathieson’s lens and the film’s detailed production design, we see Mary as the moon to Elizabeth’s sun. Mary’s windowless court feels cold, damp and isolating. To the south, Elizabeth seeks her counsel’s approval in a sunny stone hall where a wooden table and benches, as if united together against Mary’s power grabs.

However, the movie is not without its flaws. There are a number of overextended reaction shots to the ladies-in-waiting of both camps, causing unintentionally awkward pauses in the action. In these moments, the ladies don’t do much except stare at the queens as they act out or cry, but why aren’t we watching the queens during these moments? The cynical part of me worries that this may have been a creative choice to emphasize the diversity of the supporting cast, which is great but shouldn’t come at the expense of the movie’s craft. The actors are better served when given something to say or do, like the candid scene when Mary is talking to her ladies-in-waiting about what it’s like to be with a man or when she confronts her fiddler, David Rizzio (Ismael Cruz Córdova), for betraying her.

Poor Margot Robbie is not the fairest queen in the movie. The actress is saddled with a heavy prosthetic nose and pox marks for what may be the least glamorous cinematic interpretation of Elizabeth I. Despite the film’s bid for authenticity, no other extra or supporting character has anywhere near a grizzled visage as Elizabeth, making Robbie’s face an anomaly. Robbie, however, plays the paranoid and tortured queen well, using a tense, nervous energy against Ronan’s cool and cutting performance.

There are many reasons why Elizabeth I’s reign overshadows Mary’s story: Elizabeth avoided taking a husband, which helped cement her power while Mary’s many partners cost her her reputation; Elizabeth also survived the political maneuvering, illness and even her cousin’s attempt to form a rebellion against her while Mary lost many times over in her life. “House of Cards” showrunner Beau Willimon draws out every possible bit of historical intrigue from the saga, shifting power dynamics and backroom deals in his script and giving Mary’s story a faint pop feminist twist. Mary is now the queen who leaned in and lost. The movie becomes a story of two leaders bound by sovereign duty, hindered by their gender, pitted against one another for the crown and want of children. It doesn’t always work, but the film makes for an entertaining argument to reevaluate the legacy of Mary Queen of Scots, beyond the time-worn focus on her tragedy.