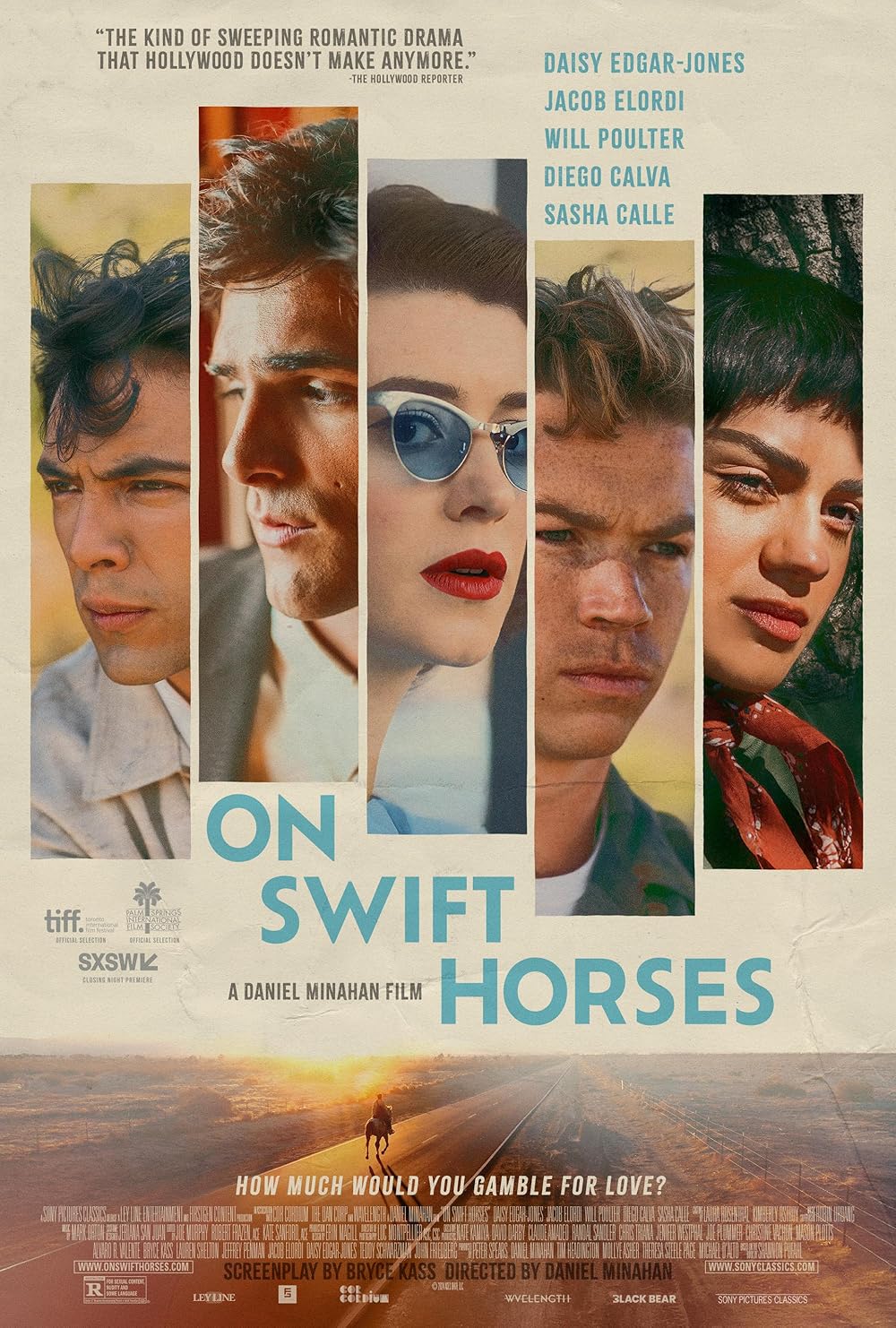

Daniel Minahan’s “On Swift Horses” follows two allies on parallel journeys through a difficult world. Told in a style that could be called old-fashioned due to its lack of cynicism in an era when heartfelt melodrama is often mocked more than celebrated, it’s fair to call this engaging drama a throwback, a movie that wants to sweep you away on the back of its passion and heartbreak. It mostly succeeds, thanks in large part to a phenomenal young cast, led by the best film work to date from one of the hottest actors of his generation in Jacob Elordi, who finds the perfect vehicle for his Montgomery Clift-esque good looks, using his magnetic screen presence to barely hide the roiling emotions underneath. Possibly due to fealty to the source, “On Swift Horses” stumbles a little bit on its way around what feels like an extremely rushed final lap, but this is still a winner.

Daisy Edgar-Jones stars as Muriel, a young woman starting her life in her mother’s home in Kansas shortly after the Korean War. Her veteran husband Lee (Will Poulter) is a decent, hard-working man, but one senses a sort of incompatibility in their relationship right from the beginning, and it’s not just because Muriel hides a pack of cigarettes from him in one of the first scenes. This is a film about two characters who hide more than just smokes, living lives that they can’t show even to those they love the most.

Muriel’s counterpart in this tale is her brother-in-law Julius (Elordi), who comes home from the war in a state that feels somewhat aimless, introduced shuffling a deck of cards as he walks down the road. In one of his first scenes, he teaches Muriel how to play poker, imparting knowledge about staying ahead of your opponent, even if it requires cheating. Julius is a man who seems almost confidently unmoored, the kind of wandering soul who takes what the world presents him in any given moment and then moves on to the next. In a sense, he’s the opposite of Lee, a man who wants to buy a home in California and follow the script of the average nuclear family in the middle of the last century. Julius doesn’t believe in scripts.

And that’s how he ends up in the gambling meccas of Nevada, where he gets a job working security at a casino, literally watching people through two-way windows in the sky. He is a character introduced by cheating at cards that also carries sexual secrets who now becomes a soldier in a war against people like him. Bryce Kass’ screenplay, based on the book by Shannon Pufahi, contains so many of these wonderful dualities, a more complex endeavor than your average melodrama.

In the sweaty attic above the casino, Julius meets Henry (Diego Calva of “Babylon”) and falls passionately in love. Meanwhile, Muriel meets a neighbor named Sandra (Sasha Calle) and begins her own infidelity. She also feels the kick of gambling, overhearing tips on the horses at her waitress job and turning them into a nice return that she keeps from her husband. Gambling secrets intermingle with sexual secrets in a film that’s consistently captivating in terms of its storytelling, even as the script is forced into a few too-tidy resolutions in its final act.

The first hour of “On Swift Horses” is one of the best film hours of the year. Elordi imbues Julius with a marvelous mix of swagger and vulnerability, finding a tenderness beneath a guy who always seems a step ahead of the world around him. When he meets Henry, Elordi plays the love affair perfectly, realizing that Julius sees some of himself in Henry too, and so he knows the dangerous path down which this more reckless version of Julius is heading. When Henry tries to push back against the walls of a system he’s now supporting, tragedy feels inevitable, and Elordi does so much with a look or a choice of body language. He’s been good before in films like “Saltburn” and “Oh, Canada” but this is his best work to date.

He’s matched by strong performances from Edgar-Jones and Poulter too, and Minahan and cinematographer Luc Montpelier give their performances a lavish visual backdrop that some have compared to Douglas Sirk, although Sirk would have turned up the reds and yellows in a color palette that’s largely brown. Still, the comparisons to a filmmaker who embraced outsiders and understood the magnetic pull of watching gorgeous people play melodrama to the back row of the theater are valid. This is a film for people who miss that era of Hollywood. And I wish there were more like it.