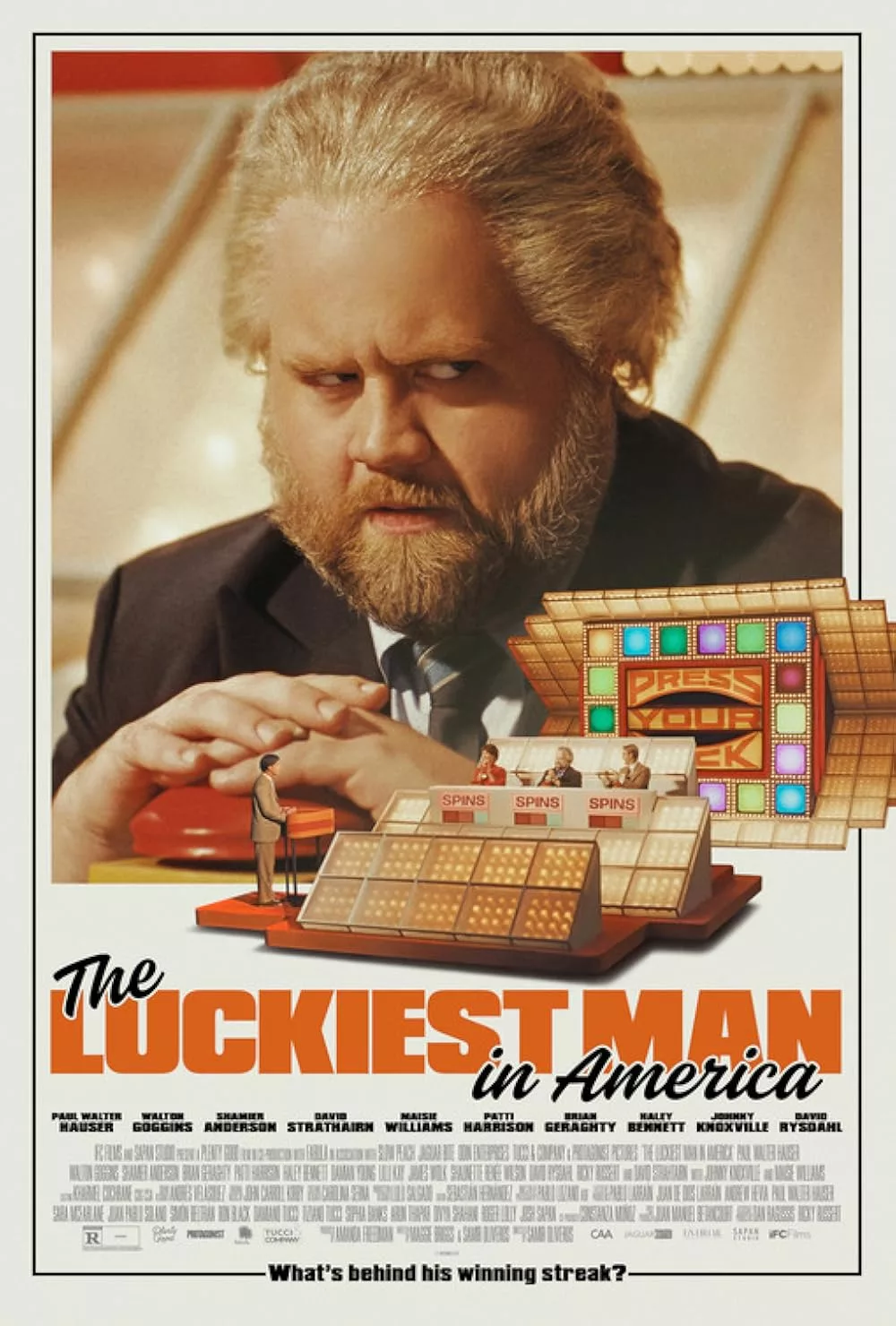

In 1984, an ice cream truck driver and experienced scam artist named Michael Larson went on a CBS game show called “Press Your Luck,” which was predicated on contestants pressing a button to stop a “randomizer” that determined how much money they won. Larson had spent three months studying videotapes of the show. He’d figured out that there were only five configurations of flashing lights on the board, and that if he memorized them, he could beat the system.

The people who ran the show figured out that Larson’s run of luck was something else. But by that point he’d already won $110,237, over $300,000 in 2025 money, and the audience was thrilled. So the question became: do we try to punish this man for cheating, or keep the deception going and try to make money from it ourselves?

“The Luckiest Man in America” is written and directed by Samir Oliveros, who learned about the subject through life’s randomizer: he bought a used videotape at a thrift store that had episodes of “Press Your Luck” on it, became fascinated by the show, looked up the history online, and found out about Larson’s scam. The result is a tight (90 minute) study in characterization and ethics in which Larson is played by Paul Walter Hauser (“Richard Jewell”), an excellent actor who is also listed as an executive producer.

“The Luckiest Man in America” is good follow-up viewing for “Quiz Show,” a drama about the 1950s quiz show scandals that prompted congressional investigations and led to reforms in the television industry.

It’s also an example of how to make a low-budget movie that immerses you in a long-gone world and the minds of people who lived in it, while maintaining a tight geographical focus on a small number of characters. Probably eighty percent of the movie takes place in the game show studio, the control room, and various hallways and rooms at CBS Studios in Los Angeles in 1984. There’s one scene where a panicked Larson, who is starting to think everyone’s on to him, goes out into the parking lot and interacts with security guards, and you see some vintage cars. That’s all the movie can do in terms of dazzle-dazzle, and that’s fine, because the real show is psychological.

The cast is remarkably accomplished for such a small production. Walton Goggins nails the demeanor and cadence of the host of “Press Your Luck,” 1970s game show staple Peter Tomarken — something Goggins probably didn’t need to bother doing, considering that almost nobody under 50 knows the man’s name anymore, but that is much appreciated for the dedication it must have required. He also creates a solid, believable “showbiz pro” energy; you see that Tomarken is as serious offscreen as he is cheerful when cameras are rolling. The performance is another winner in a 25-year stretch that has produced one great performance after another, from “The Shield” and “Justified” through “The Righteous Gemstones” and “The White Lotus.”

David Strathairn costars as the show’s producer, TV executive Bill Carruthers, who specifically recruited Larson because he found him odd and interesting and had made a promise to himself that his contestants would have enough personality to keep people coming back no matter how the contest was going. Strathairn is one of those actors who can play everybody from saints to scumbags, but somehow, no matter how many times you’ve seen him act, you still don’t know what you’re getting until he shows you. He does it again here. While not entirely good or bad, Carruthers is not winning any prizes for business ethics. His genuine excitement over giving viewers a good show is interwoven with a ruthless commitment to pleasing bosses and advertisers. Strathairn uses his understated charm to keep surprising you even as Carruthers finds a way to say yes to every moral compromise that’s introduced (often by a CBS network executive played by Damian Young—another character actor who’s damn near perfect in every role, including the kindhearted sugar daddy in the recent indie comedy “Fu*ktoys”).

Oliveros’ direction has flashes of late 90s-early aughts-vintage American indie filmmakers like Paul Thomas Anderson, Sofia Coppola and Darren Aronofsky, who used subjective editing and sound techniques, dynamic camerawork, and disorienting music to create a feeling of intense pressure even when the actions being depicted onscreen were unremarkable in themselves. The film’s midsection plays like the quiz show scenes in Anderson’s “Magnolia.” The fuzzy-edged synthesizer score by John Carroll Kirby contributes mightily to the feeling that you’re watching people who have no idea what the Internet is. It also suggests that these characters are small in the greater scheme, but have gigantic feelings. It’s like the music is rooting for them to be their best selves even when they’re failing.

Hauser is the star of the movie, and his performance is the central organizing element for the script—a portal through which all the film’s action and our thoughts about it must pass, and a kind of organizing principle for any statements the movie might wish to make. Larson is another short-list performance by an actor who already occupies a unique place in American cinema. He has an implosive intensity. He’s not innately cartoonish or even particularly emphatic (unless the role requires it). But he’s magnetic even when the performance is minimalist or withholding, which is the case here, as much of a mess as Larson can be.

Intense emotion emanates from Larson at all times. Hauser makes sure that you feel it, without signaling precisely what it means from one moment to the next. Sometimes you look at the character and think “something is wrong,” but not whether it’s a sudden attack of guilt, a tactician’s icy concern that he’s about to be found out, or a false flag meant to throw off onlookers so that he can accomplish a secret goal.

Hauser is fair to Larson as a person even though he doesn’t indulge in any special pleading for sympathy. We believe Larson when he says he loves his daughter and is only doing this to get on TV and recapture her esteem after letting her down. But we also know that’s a self-serving cover story, and we suspect that Larson knows it is, too. Hauser gets all of this across without making a big deal of it. It’s less a chameleonic transformation than something more akin to Silly Putty picking up the details of an illustration it’s been smushed against.

The only major problem with “The Luckiest Man in America” is that, after a certain point, there isn’t a whole lot to discover, or even chew on. Once it’s been established that Larson has found a way to game the system in a way that is difficult to label as “cheating”—since it’s about exploiting a weakness in the series itself rather than breaking established rules—all that’s left is watching the people assigned to the show debate how to respond to the deception. Since the milieu is so nakedly cynical, it’s not a huge shock when they decide to turn a potential embarrassment into an opportunity. And then you’re mainly left watching the acting, camerawork, and production design, and listening to that endlessly delightful score.

Is the movie carrying itself with a bit too much momentousness, given the “historical footnote” nature of the subject? Yeah, probably. Blowing the lid off the mendacity of television isn’t the flex that it was fifty or even thirty years ago. Nor is using a bit of popular culture as a gateway to examine the endemic corruption that has characterized the United States in all its manifestations, even as it put forth an image of immaculate righteousness around the globe.

But “The Luckiest Man in America” is still an impressive display of filmmaking chops, with superb actors, including “Game of Thrones” costar Maisie Williams as an assistant and guide who struggles to maintain neutrality, and Shamier Anderson as Chuck, a producer who is dragooned into becoming a sort of makeshift private investigator looking into Larson’s past and trying to intimidating him. (A scene where Chuck intimidates Anderson in a hallway is a highlight of the movie.) And it resonates with what’s going on in the world circa 2025—a debased time in which, for too many people, the first question prompted by any halfway interesting life event is “Can I monetize this?”