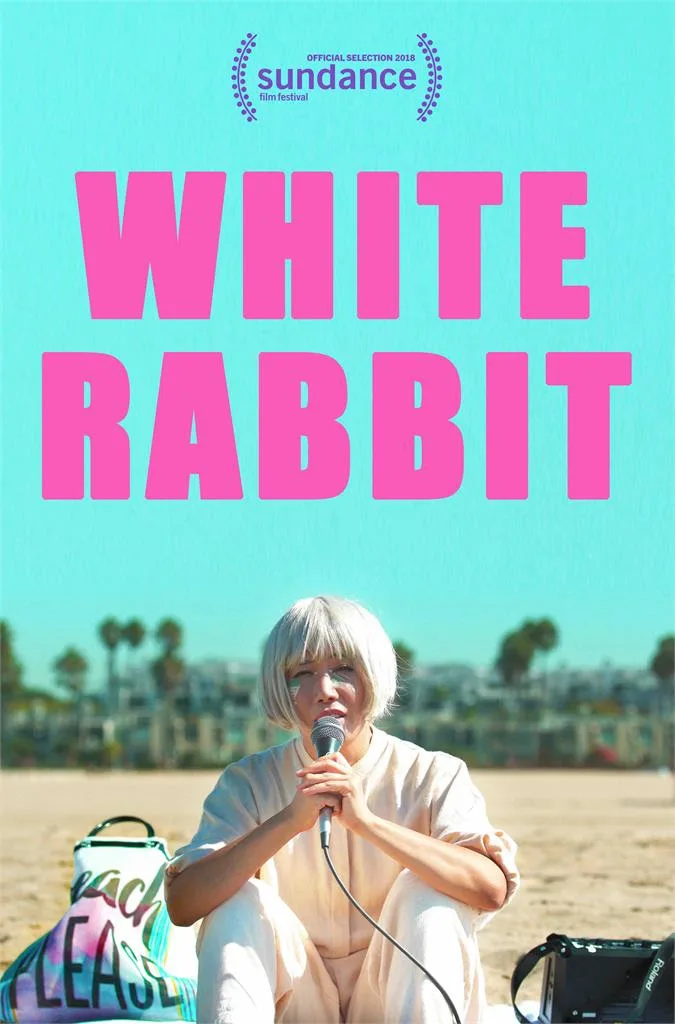

There’s no “Written by” credit at the end of “White Rabbit.” Instead, a “Story by” credit goes to the film’s two defining creative forces: director Daryl Wein, and his star, central figure, and main cause, Vivian Bang. As a loose L.A. story that wants to riff on what it’s like being Vivian Bang just as much as selling you Vivian Bang and her talents, it can be a battle between his vanilla direction and her multifaceted charisma. But even if “White Rabbit” feels like the ultimate acting reel, it’s albeit for a talent you immediately start to root for.

The “story,” such as it is, contains some days in the life of Bang, a Korean-American performance artist (creating things “you can’t sell”) who makes money working for TaskRabbit, a real app where people enlist other human beings to do household tasks. Meanwhile, Vivian’s relationships draw out her emotional highs and lows, as she deals with the pain of an ex-girlfriend and the excitement of a new love interest in Victoria (Nana Ghana), a photographer who sees Vivian perform a monologue in park about Korean-American stores being destroyed during the L.A. Riots. Whatever scene she’s in, Bang proves to be an actress with distinct definitions of “performing” as opposed to “acting,” and has fashioned a magnetic presence out of her ability to go between the two.

Bookending the film and sprinkled throughout, Vivian’s performance art scenes are the film’s best hook, as we observe her abrasive, alien presence. In the opening scene, she’s standing in a Whole Foods with a microphone and carrying a small amplifier, in a white wig and jumpsuit, speaking in broken English about an immigrant’s experience. Wein’s camera does not care who is listening, it’s more that she’s simply doing it. And when she gets home, Vivian takes off the costume and becomes another character, letting her hair down and putting on a purple sweater, so that she can film herself mashing her face into a pile of Cheetos. While these are the strangest scenes Wein’s film has to offer, here is someone on her own wavelength, welcoming us into her exhilarating, free-spirited creativity.

Early into the movie, Bang is contacted by a young white male director after he sees some of her work. The red flags fly: he panders to her by repeatedly calling her “powerful” and saying that she’s lucky to have something to overcome, attacking himself for being privileged. It’s a successfully teeth-gnashing set-up for Wein to hit head-on his status as a white male director telling Bang’s specific story, but also for Bang to touch upon the meetings and roles she must have taken as a hustling actor in real life, as with her bit appearances speaking broken English in roles like “Yes Man” or an episode of “Sex and the City.” As this arc happens early into the movie, it allows the story to then move impulsively, without Wein’s gaze having any rose-tinted perspective.

For a stunning central screen presence who cannot be defined by any one of her characteristics, the story tries to extract many of her elements through conversation. It makes for rare spectacles, like seeing two women of color talk about being artists and struggling to make money, or about the experience of being hyphen-Americans. Like Vivian’s monologues, the scenes are direct in their significance, but a fuller idea of her is painted: a woman who was born in Korea and learned English from John Hughes movies. Now, she’s someone who occupies her own space somewhere between down-to-earth and completely funky.

But there’s a straight-laced quality about Bang that Wein’s direction overestimates, the dialogue-driven scenes running parts of “White Rabbit” dry with his simple volley of two camera shots, depending on who is talking (Wein’s best addition is probably the soundtrack, which makes effective use of standout artists like Francoise Hardy and Big Thief). It’s a further reminder that when a movie is designed to promote a new talent, like Josephine Decker’s recent “Madeline’s Madeline” and future star Helena Howard, the star talent should be the film’s visual spirit animal. The qualities of “White Rabbit”‘s direction are too standard, forgettable—words we learn quickly that could never apply to Bang.